In which direction did megaliths spread?

The recent view

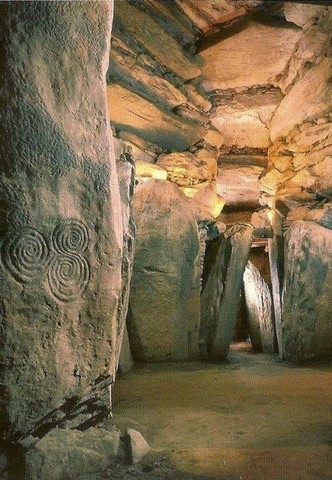

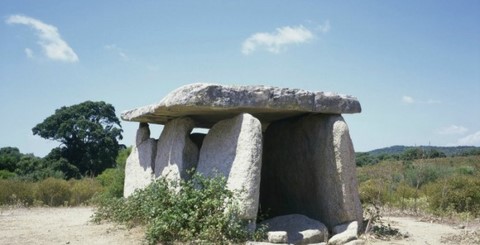

Dolmen of Crucuno, Brittany

Monumental stone tombs, stone circles and rows of stones are to be wondered at in many places in Europe. These constructions made of rough blocks of stone were created thousands of years ago – some 35,000 of such sites have been preserved. Even some menhirs, known to fans of the comic-strip hero Obelisk, can be seen here and there in the landscape.

Whence came this passion for stones, the remnants of which can be found not only in Scandinavia, Germany and the British Isles, but also in Southern Europe?

Researchers have now found evidence that the trend for megaliths started in Northwestern France. From there, the use of large blocks of stone to build tombs and mark places of worship spread along the coasts of the Atlantic and of the Mediterranean, according to Bettina Schulz Paulsson of the University of Göteborg in the Proceedings of the National Academy of the Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS). She emphasizes that the technical abilities of humans in the early phases of this development some 7,000 years ago were considerably more sophisticated than had been presumed up to now.

A little later the first monumental tombs in the shape of round burial mounds came into existence in Brittany – such as the huge burial mound of Saint Michel at Carnac, which contains a closed stone burial chamber and is about 6,800 years old. Other buildings originated during this same phase in that same area, typified by closed stone burial chambers. Somewhat younger are similar sites in the Northern Mediterranean – in Catalonia, Southern France, on Corsica, Sardinia and in Northern Italy.

An innovation occurred around 6,300 years ago, and again in the west of France: the first all stone tombs, the so-called dolmen, and corridor tombs, which were no longer closed, so that humans could be buried there over several centuries. The scientists cite as an example the hill tomb of Péré near Prissé-la-Charrière in New-Aquitania and Lannec er Gadouer in Brittany.

During the next phase, which started around 6,000 years ago, such compounds spread to the British Isles as well as to other areas in Western France and on the Iberian peninsula. This suggests that the spread occurred by way of the sea. “Their spreading stresses the relationship these cultures had with the sea and the spread of burial traditions by seaway,” the author writes.

"The older generation of archaeologists was right about the maritime diffusion of the megaliths concept,” she judges. “But it was wrong as to the region of origin and the direction of the diffusion.”

Her study shows that the mobility as well as the technical abilities of humans 7,000 years ago have been clearly underestimated and she calls for a radical new estimation of this period.

But Martin Bartelheim at the University of Tübingen doesn’t see things that way: that humans carried on coastal navigation 7,000 years ago is well known. As for the conjecture about the megalith culture originating in Northwestern France, it is “not inconceivable.” " It has been accepted that the sites in that region are very old," said the researcher from the Institute of Ancient and Early history. “the C14 tests have now confirmed this.” However, the results remain under caveat. For there also exist megalithic structures in North Africa, as in Egypt, Libya, Tunesia and Morocco. These have hardly been dated up to now and were not taken into account in the analysis.

Walter Willems

Translated from the German by Anne-Marie de Grazia

See the original article in Der Spiegel, Debruary 13th, 2019

In fact, the results of the Carbon 14 tests have been available for a long time, and this "confirmation" does not date to just right "now," contrary to the statements of the expert from Tübingen. Readers of Q-MAG.org know the French essayist and polytechnician Jean Deruelle (1905-2001), a mining engineer who was the director of the Houillères de Lorraine (Coal-Mines of Lorraine). In 1999, and even earlier, in 1990, he had studied the results of the C14 datings of the megaliths, and undertaken the "radical new estimation" Bettina Schultz Paulsson is calling for, and drawn the inescapable conclusion called for by mainstream radiocarbon dating, and which mainstream experts today are still shy to face: the culture of megaliths spread from Northwest far to the South and East, predating the monumental buildings of Egypt, Mesopotamia and Mycenae. In 1999, in his book L'Atlantide des Mégalithes, (Editions France-Empire) Jean Deruelle writes the following:

Jean Deruelle: The megalithic empire

...But how are we to present this other, so much different, facet of the history of Europe? The “humans of the megaliths” left practically nothing besides their enormous blocks of stone to signal their passage on Earth!

Should we be surprised that for a long time their fate hadn’t aroused anybody’s interest? To the peasant, a dolmen in the middle of his fields was merely a hindrance, associated with some superstitious fear. Didn’t the Middle Ages see in them the work of the Giants which the Bible incidentally mentions? Many a best-selling author threw in some extra-terrestrial levitation technicians. In the XIX century, these works were considered to be posterior to the Roman period, because Caesar did not mention them.

But archaeological progress between the two World Wars compelled researchers to acknowledge the amplitude of a phenomenon which stretched along the whole Atlantic façade of Europe, displaying, here and there, architectural refinements which were apparently out of the reach of primitive populations. But one found oneself compelled also to push back their dates farther and farther up in time. Someone dared to propose -1,500 BC. It was said that the autochtonous populations must have tried to copy, uncouthly, the “cyclopean” walls of Mycenae and its corbelled cupolas, these “tholos” of which the Treasury of Atraeus furnishes the best example.[Glyn Daniel, Les Monuments mégalithiques, Pour la Science (1980); The Prehistoric Chamber Tombs of France (1960); The Megaliths builders of Western Europe (1963). ]

This date appearing too short, yet older masters were called for, who might have come from Crete around -2,000 BC – where, to be honest, megalithism is hardly present. Finally, the presence of numerous small dolmens on the Golan Plateau, in Syria, brought one to imagine that the origins of this type of architecture must be put, in some form or another, to around -3,000 BC, in the Eastern Mediterranean.

This direction of the diffusion of megalithism was accepted by all specialists. In 1970 still, the chain: Aegean Sea, Malta, Andalusia, Portugal, Brittany, the British Isles was considered an essential axiom of prehistory [Colin Renfrew, Problems in European Prehistory, Edinburgh University Press, 1979, p.8-9, 350-352, and Les Origines de l'Europe, Flammarion, 1973, 1983, p.52 ].

Radiocarbon dating now compells us to accept that most megalithic works were built between -5,000 and -2,500 BC, long before any Minoans, or even Egyptians can be brought in. Such a revision seemed harrowing to many a humanist. Even more incredibly than had been the case for the Danubians, one now had to grant anteriority to these uncultured barbarians of the West!

The duty at hand, in any case, was to engage in a very pecular research effort in order to delimit the contours of this unexpected civilization, the existence of which hung on the threads of a few measurements of radioactivity. The first results were discouraging! One had attributed to megalithism the sumptuous “princely tombs” in the vicinity of the most beautiful megalithic monuments, especially those of Wessex, in the Southwest of England and in Armorique, in the North of Brittany. By placing them after -2,500 BC, radiocarbon dating satisfyingly confirmed their placement in the Bronze Age, already assured by the nature of the objects they contained.

But it follows that these vestiges brought no information about the megalithic civilization of the neighboring megaliths builders, who were much older.

Everything had to be taken up again from the bottom, these enigmatic stones needed to be brought to speak. And one needed to make out in the ground the slightest clue which would allow to throw a light on the way of life of their builders.

In order to clear up an overview, one needed to first establish a complete chronology of the archaeological facts. The task was an aduous one because, for these far-off epochs, radiocarbon dating is valid only at + or - 200 years. One must therefore establish a mean between several measures, an uneasy task in the case of buildings which were used and remodelled over one or two thousand years. Moreover, Thomas was dismayed to note that authors continued, in writings published in the 1990s, to date the relevant events to the "Middle Neolithic” and to present radiocarbon datings without making clear whether they were brutto results or calendar values which, after calibration can differ by some 800 years of correction.

One could only leave to their fate the inhabitants of Eastern Europe and of Mesopotamia and go very far back to examine what was happening around -5,000 BC in the West and in the Mediterranean.

At this time, neolithism had already been installed for a thousand years in the Danube Valley and had brought forth to the North the homogeneous zone of the so-called banded, or linear ceramics, which stretched all the way from Ukraine to the Paris Basin, and even to Normandy. Thomas also knew that another Neolithic current, named cardial, simultaneously progressing from the Mediterranean through Languedoc, had reached the Vendée [Jacques Briard, Les mégalithes de l'Europe atlantique, Ed. Errance, Paris, 1995] in France as early as -5,300 BC. The West, therefore, had benefitted of this technical progress much earlier than had been thought. And there is more! Whereas at this time Mesopotamia and Egypt were quasi deserted, archaeologists had the surprise to discover in the Paris region, under enormous tumuli over one hundred meters long, graves that were apparently reserved for the chiefs of a numerous, organized and hierarchized society. In Brittany, the great tumulus of Saint-Michel at Carnac is an imposing example.[J. Briard, ibid., p.19]. But these were made of earth. It’s around -5,000 BC that the first megaliths begin to appear in Bretagne.

Thomas was thrilled. The Bretons had distinguished themselves. To the Bretons is owed the oldest monument in Europe, maybe in the world: the cairn of Barnenez, this massive heap of stones which, until recently, had been used as a quarry!

Seemingly defying the sea on a rocky spur North of Morlaix, this rectangular piece of stone-work 73 meters long piled up five stories of terraces sustained by vertical siding stones. The aspect of a funerary boat sailing towards the ocean is confirmed, to the west, by a triangular prolongation in the shape of a ship's prow. [Briard, ibid, p.32; Colin Renfrew, Les Origines de l'Europe, Flammarion, 1973, 1983, p.104; J. Briard, L'âge du bronze en Europe barbare, Ed. Les Hespérides, Toulouse, 1976, p.127].

Sure, the ziggurat of Ur was higher and more finely worked, but its sides measured "only" 40 meters, and moreover, nothing has been found inside!

Whereas Barnenez, which is older by two thousand years, sheltered eleven tombs. And, an astonishing architectural fact, the oldest of them, dated to -4,700 BC, are in the shape of corbelled vaults, three thousand years before the famous "tholos" tombs of Mycenae, which had been thought to have served as models.

And the whole country is littered with dolmens, vaulted tombs, menhirs and stone alignments.

The Bretons were not long alone. Very soon, as early as -4,400 BC, one started to build dolmens in the South of Portugal, then, towards -3,900 BC, along the Northwest coasts of Spain [J. Briard, Les mégalithes de l'Europe atlantique, p.113] and, later, all the way to Catalonia.

Meanwhile, the movement spread to Normandy, then, by way of Southwest England, to Ireland with, as early as -4,000 BC [J. Briard, ibid. p.91] , massive dolmen porticoes. Denmark multiplied small dolmens beginning around -3,800 BC. [Glyn Daniel, ibid. p.89-93; C. Renfrew, Problems in European Prehistory, p.275, and Les origines de l'Europe, p.105; P. Bosch-Gimpera, Les Indo-Européens, Payot, 1961-1979, p.140]. Megalithism gained the Massif Central a little bit later, (the Grand Causse counts around one thousand dolmens), and slowly spread to Languedoc, and even to Provence.

"How," Thomas wondered, could one fail to be amazed by the immensity of the space conquered by the humans of the megaliths!"

And then, thinking better: "I am not sure that the word 'conquest' is apt, because one cannot find in this whole region any traces of combats." But surely, the term "immensity" could not be contested, for megalithism spread yet further, to Southern Spain all the way to Andalusia, and, to the North, to Scotland all the way to the Orkney Islands.

Megalithism is evidently a major phenomenon in the history of humanity. Through its spread, but also through its continuity and unity along a vast amount of time, the proof of which being the quasi identical character of the monuments dotting its course.

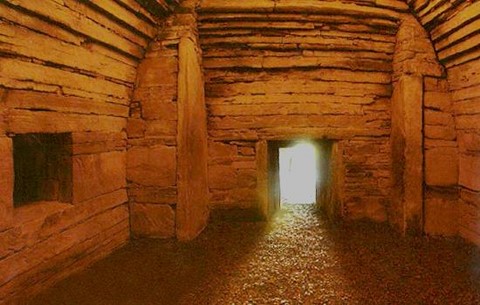

The old Barnenez tumulus already covered "tholos" tombs (with corbelled vaults). The hall is surrounded by a circular wall the successives bases of which, made of flat stones, are in slight overhang over the one preceding, so that the diameter of the work diminishes, creating the shape of a rounded vault, closed by a finishing plate of stone. Numerous examples of this are found in other places. The most famous is the one of Newgrange, in Ireland. The access corridor is 24 meters long and leads to a chamber of 5 m by 6 m, the vault of which, culminating at 6 m, is superb (pictures below). The jointing of the stones is so finely executed that it is still perfectly water-proof. The whole work is covered with a tumulus 90 meters in diameter, 13 meters high, surrounded by a three meter-high wall. [J. Briard, Les mégalithes de l'Europe atlantique, p.99].

And there was more to admire. Newgrange is at a distance of 500 km from Barnenez. And what does one find 500 km farther North, at Maes Howe, in the Orkney Islands, off the North of Scotland? Almost exactly the same building as in Ireland, under a tumulus 35 meters in diameter. The perfectly jointed corridor leads to a chamber, the vault of which reached over four meters [J.Briard, ibid., p.81]. (Picture right)

And, to the opposite end of the megalithic world, 1,500 kilometers from Barnenez, there are dozens of monuments of this type spread over the South of the Iberian peninsula. To the North of Malaga, for instance, the Cueva de Romeral hides under a tumulus 85 meters in diameter a 20 m corridor leading to a tholos 3.80 meters high, [Ibid., p.123], incontrovertibly similar to the one in the Orkneys, 2,500 kilometers away!

How can one claim that this is due to the chance of independently evolving cultures! It is not by mere chance that populations succeed in maintaining such cohesion over such a large space for such a long time. For, if Barnenez was built around -4,700 BC, Newgrange, Maes Howe and Cueva de Romeral date to -3,300 BC and were in use down to -2,500 BC [Glyn Daniel, p.93; M.O. Kelly, in C. Renfrew, The megalithic monuments in Western Europe, p.118)

Such a vast territory was necessarily organized under the authority of some cutural and political hierarchy, meaning, it had to have the character of a true empire which, for 2,500 years, ruled over the whole atlantic façade of Europe.

This organization has left no documents, none of the usual traces of the power of kings. Yet archaeologists are becoming more and more convinced of its existence and of its extraordinary capacities.

From: Jean Deruelle: L'Atlantide des mégalithes, éditions France-Empire, Paris, 1999. Extracts from pp.164 to 171.

Translated by Anne-Marie de Grazia

by Jean Deruelle, in Q-MAG.org: