Nathan Katz: Annele Balthasar

a play about the witch-hunts in Renaissance Europe - first performed in 1924

translated from Alsatian into English

Performed for the first time in 1924, S’Annele Balthasar is a dramatic poem about the witch-hunts in Europe at the time of the Renaissance, written in Alsatian by the French Jewish-Alsatian poet Nathan Katz (1892-1981). It plays in the Sundgau region of southern Alsace in 1589 and is based on the records of the witch-trial of a young peasant girl of the area. It was recently translated into French by Jean-Louis Spieser and published in a bi-lingual edition by Editions Arfuyen in the wake of a vigourous renewal of interest in the poetry of Nathan Katz. The High Alemannic form of the Alsatian language in which Nathan Katz is writing is actually my birth language, and I was lucky enough to meet the poet himself in my childhood. I have translated S'Annele Balthasar into English and modern German, hoping to help it sail safely into the literary future.

Anne-Marie de Grazia, October 2023

to the play:

for stage and performing rights, please address yourself to:

c o n t a c t @ a r f u y e n . c o m

From Act III, at the Court of Malefices

(...)

President (to Annele): You must now give an answer to our questions! You confess that you have dedicated yourself to the Evil Spirit, and that you have been at Fulleren on the Fuchsberg, to take part in a witches’ dance.

Annele: Seven judges sit at court... years pass by... years are gone... Seven skulls rot in the earth...

President: You must answer what you are asked!...

Annele: But I am but a poor maiden from Willer... And now you want to hurt me... with you rough hands! (Suddenly screaming) How dreadful it must be inside the grave!... In this humidity, out there!... But not even that!... to burn by one’s living body!

President:

When did the Evil Spirit come to you? Now, answer!

Annele: He came to the little window... Don’t be so wild, you bad boy... what if you break a windowpane... what then!

(Starts laughing) But don’t be so wild, I say!... - You’ve stolen a little carnation from the windowsill!... Oh, you’re so sly, you!... You only wanted to make me come outside, to scold after you!... I knew it!

President:

You went sometimes to the witches’ dance?

Annele: I had no more peace, day or night!... He screamed for me! He whinnied above the barn roofs! He has torn apart trees! I was lying so warm under the bedcover!... I, pretty Annele... I was awake... when he sometimes whispered sweet things from outside, as if a breeze were going through a thicket of peonies stalks!... I heard him the whole night! I cried in my pillows!...

President: You have gone with them onto the Mountain of the Fox!

Annele laughing: Juchu! Juchu!! We rode through the night... out through the chimney... on the broomstick! Like the wind! Juchu!... Riding over the churchyards... over the woods, over the villages! – – At Old Ferrette, we have danced around the gallows! As fast as the wind! Just like the wind! – – Isn’t that a merrymaking, my sweetheart, my betrothed... Haha! Over the woods, over the dells, over the dark villages, all over!... Naked we danced under the pines! The little owls were shrieking for us... The dogs whined... After that, someone died in the village.

President: You confess that on the order of the Evil Spirit you have done harm to the people of the village?!

Annele: There he comes, that Doni!... Over there!... I knew that he would come to help me! He is so strong! He knows so much! I knew it, he had to come!... Won’t you, even if your folks won’t have it, won’t you stand by me?

President: Listen to what you’re asked! At the home of Peter Lütz, you have done harm to a child?...

Annele; It was so pretty in its crib... it laughed...

President: You took it on your arm! After that, it lay for four weeks, grabbling with death!

Annele: Poor child! How it grabbled!

President:

At Klaus Kampf’s, you’ve walked through the stable?

Annele: The stable at the Kampf Klaus’!... So good warm... The trough of cut hay, there!... Through a window, a weeny bit of light... The chains jingling. The beasts were ruminating.

President: After that, three calves were done in.

Annele: These poor calves!...

President: You confess to bewitching the stable?

Annele: They were standing there so humbly, and sickly, the calves!

President pensively:

Write that down!

(...)

to the whole play: Nathan Katz: Annele Balthasar (in English) pdf

I took it upon myself to reduce to a minimum the extensive scenic indications given in the original, which were destined to an amateur theater and -actors of one hundred years ago. Those who are interested in the full scenic indications can find them here: nathan katz: annele balthasar (with full scenic indications)

also available in a translation by me into modern German:

nathan katz: annele balthasar (auf Deutsch)

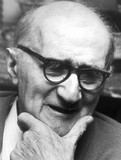

Nathan Katz

Nathan Katz was born on Christmas Eve 1892 at the Southern tip of Alsace, near the city of Basel and the Swiss border, in the village of Waldighofen (population then: ca 750 inh.), the son of kosher butcher Jakob Katz and Jenny Schmoll (his birth house, picture). Alsace, at the time of his birth, following the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, was part of the German Empire. He studied at the village primary school, got entranced in reading stories of Buffalo Bill and the “Indian” novels of Karl May, which he found at the village store, until the local priest had them decried from the pulpit as “trash” literature. The store-owner replaced them with a stack of German classical plays by Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805) and little Nathan devoured now these instead.

Retail meat was sold at the time wrapped in newspaper, with which the family butcher shop was regularly supplied by a rag-collector working in the nearby city of Basel. Nathan would cut out all the literary articles, and salvage the literary magazines, German and French, for his own consumption. He got acquainted this way with Rainer Maria Rilke, Charles Péguy, Rabindranath Tagore, Frédéric Mistral...

He started work at age 15 as an office apprentice at the local textile plant. A friend who studied at the close-by Altkirch teachers’ school made him acquainted with the Greek classics, Sophokles, Aristophanes, Plato, as well as with Oriental and Asian poetry: Hafez, Kalidasa, Li Bai, Du Fu, and the Western classics, Goethe, Hölderlin, Heine, Shakespeare, Baudelaire, Balzac and, especially, his beloved Racine. At school, he had been introduced to Alemannic poetry through its foremost poet, Johann Peter Hebel, (1760-1826) - whom Goethe and Tolstoi had admired.

He is drafted into the German Army in 1913 and mobilized right from the first days of World War I. He is seriously wounded at Sarrebourg three weeks into the war, in danger of losing an arm. He is sent to convalesce for three months in Freiburg-im-Breisgau, across the Rhine from Alsace, where he seizes the opportunity to study Alemannic literature with Philipp Witkopp as a free auditor at the university.

He is re-mobilized shortly afterwards and in March 1915, he is sent to the Russian front. He is taken prisoner two months later and interned for fourteen months at a camp near Nizhny Novgorod. The Russians considered Alsatian prisoners of war, even under German uniform, to be Frenchmen, i.e. allies, and the conditions of his detention allowed him to carry on a love affair in the nearby village and to write, in German, his first book of poems, the pacifist: Das Galgenstüblein (“The Little Chamber with a View onto the Gallows”). It would be published after the war and promptly translated into Russian and Armenian.

He is repatriated to France via Arkhangelsk in August 1916, imprisoned in a French camp as an enemy (German) soldier upon arrival, and put to work in a factory of military equipment in Saint-Etienne. He is then interned in a prisoner camp for Alsatians and Lorrains near Lourdes for an additional 18 months. He is freed to return to Waldighoffen in September 1919, after four years of detention, almost three of them in France.

He joins work at the family butcher shop. He seems at that time to have had a deep involvement with a local peasant girl, thwarted by families, probably on both sides, because of his Jewishness. It was to trigger his life-long love lyric, and its deep heartbreak almost certainly inspired his play S’Annele Balthasar, which is produced in 1924 by the Théâtre Alsacien de Mulhouse (TAM). He becomes part at that time of an intellectually stimulating and active group of young Alsatian artists and poets, by no means quaint or rear-guard, gathering around a young industrialist of Altkirch, René Jourdain, comprising a.o. the painter Robert Breitwieser, the Alsatian-Jewish poet Maxime Alexandre, the Breton surrealist poet Eugene Guillevic, who had taught himself Alsatian.

By then Katz has become fluent in English, and even taught himself Provençal, and has been translating into Alsatian poems by Robert Burns, Edgar Allan Poe, Shakespeare, Byron, as well as Frédéric Mistral.

In 1923, he becomes a travelling salesman for the Société Alsacienne de Constructions Mécaniques (SACM) of Mulhouse (which would become Alstom...) He travels extensively over all of industrialized Europe. When the economic crisis of the early 1930s hits, he finds himself jobless for an extended period. He finds new employment with Ancel, a newly founded bakery-supply company in Strasbourg, and is now travelling around Southern France and North Africa. Three books are said to have accompanied him everywhere: the Life of Buddha, Goethe’s Faust, Ernest Renan's Vie de Jésus. He writes his Alemannic-Alsatian poems aboard trains, boats, on the corner of café-tables, in hotel rooms...

At the outbreak of World War Two, he duly reports for French military service, is mobilized again, and sent to Philippeville, Algeria. He is by now nearing 50 and is sent back “home” in 1940, except that he cannot go there, because Alsace has been re-invaded and re-annexed by Hitler, and he is Jewish. By reason of his Jewishness, he is dismissed from his job by Ancel, which has relocated to Limoges in the free French zone. Unable to work - his passport has been stamped “JUIF” by the authorities of the Vichy regime - he spends four years in hiding and in poverty in Limoges.

Returning to Alsace in 1946, he obtains a job as a librarian at the Municipal Library in Mulhouse. In 1948, he marries Françoise Boilly, from Normandy, a grand-daughter of Napoleon’s General Foy and of the portrait painter Louis-Léopold Boilly. Twenty years his junior, Françoise will never be able to read his poetry, but she will recognize it “by ear,” being a fine musician.

He died in Mulhouse on January 12, 1981, age 89.

I am indebted to Florence Siebert for many new insights on the life of Nathan Katz.

His language

Nathan Katz wrote in Alsatian, a form of the Alemannic language, and within Alsatian, in its Sundgovian variety. The Sundgau being the small, rural area at the southern tip of Alsace, near the Swiss city of Basel, in a hilly countryside which is the Northern tip of the Jura Mountains.

I myself am a sort of a living fossil in that I am still speaking this variety of Alemannic-Alsatian. Sundgovian Alsatian, I hear, has practically disappeared. Annele Balthasar has been translated for the first time into French by my compatriot, contemporary and fellow living fossil Jean-Louis Spieser in 2018. I took on the task of translating the play into English.

It appeared to me that it should necessarily be translated into modern German as well, preferably by a bona fide. German poet. Considering that it had still not been done after almost 100 years, I considered that I might as well try my hand at that translation, too.

Nathan Katz and I

My father Jules-Xavier Halbwachs (1900-1961) was the director of the Havas advertising and travel agency in Mulhouse. He was also on the board of the Théâtre Alsacien de Mulhouse. My mother, Hortense Hueber, worked in my father’s agency as a saleswoman in advertising, canvassing Mulhouse businesses for putting advertisements into local publications - the same job as Leopold Bloom's in James Joyce's Ulysses. Daily conversing with many people in many places, from one end of the town to the other, like him, and well-known everywhere.

One of the publications of which my mother was in charge was Le Journal des Ménagères, a family enterprise of the Rugé printers (it still existed in 2021!). It was at that time a small 8-page weekly, in tabloid-format, containing practical tips, recipes, knitting instructions, short fiction, cultural announcements, etc, more or less bilingual, and destined to the city’s homemakers. It was unassuming, cheap, it had an extraordinary depth of distribution and was voraciously read. Businesses were vying for access to its limited advertising space.

And in almost every issue of this modest Journal des Ménagères, on the next page before last, there was a frame containing... a poem by Nathan Katz. I would, of course, peruse the Journal, and I came to get my weekly dose of Katz poetry, between the ages of 10 and 17. It was practically the only piece of writing in Alsatian that would be regularly available to anyone reading the popular press in Mulhouse, and one of the few occasions I had to teach myself to decipher it.

My mother was also in charge of advertisements in the programs for the performances of the Théâtre Alsacien de Mulhouse (TAM), where my father had the main say in deciding what was to be played. No doubt, he must have been instrumental in the revival of S'Annele Balthasar in 1958. Mulhouse at the time had a majestic Municipal Theatre, with a full opera and concert season, complete with ensemble, orchestra, chorus, and corps de ballet. Cheek-by-jowl stood the Brasserie du Théâtre, where one went “before” and “after,” the upper floor of which sheltered the “Cercle,” the headquarters of the Théâtre Alsacien de Mulhouse. The TAM produced one or two plays in Alsatian every season, mostly popular comedies, plus a popular Christmas play, and used the facilities of the Théâtre Municipal.

I did not, myself, see S’Annele Balthasar. I was 9 years old at the time. My mother probably recoiled before the impression this gruesome story of witch-trials and witch-burning might produce on me - forgetting that I was then going to a school named after Jeanne d'Arc, the most famous of all the women victims burned at the stake...

It’s a great pity she didn’t take me, for I saw otherwise all the productions of the TAM, and had the privilege, afterwards, to accompany her to the enchanted world of the “Cercle,” which had a horse-shoe shaped table covered with starched white tablecloth, at which “everybody” sat and drank and talked and laughed and had light dishes brought up from the Brasserie.

And this is where, at least twice, if not three times, I met Nathan Katz. He would have been in his end sixties. I remember him well, especially one time, when he was sitting in the middle of the middle-segment of the horseshoe, with his back against the wall, my father next to him, and I, with my mother, sat almost exactly across from them. I was ten or eleven. Nathan Katz was the first live author, poet, and playwright whom I met, and with whom I respectfully shook hands, coming and going, as children were expected to do then. He was very shy, very attentive, with darting eyes, forever surprised. He was extremely affable. He was a little bit dry, and drab, and a little bit comical in his courteousness and gentleness. According to the spontaneous hierarchy which children establish among adults, he appeared to me to be by far the least “important” person in the room, and also the one one would feel most at ease with.

He may have looked more shy by contrast with the rest of the company, who were generally boisterous actors, just stepping off the stage, or big local political honchos - such as Emile Muller, the unmovable Socialist mayor and MP, and his Premier Adjoint, Adolphe May, in charge of cultural affairs, an intimate of my father. There would be the legendary Tony Troxler, who had played Doni, and the lovely young actress whose-name-I-don’t-remember who may have played Annele, who was his mistress, who was married to another man, and even I could feel between them the bristling of unhappy passion. There was the slim and smart and elegant Yvonne Gunkel-Holliger, and the hearty Freddy Willenbucher, and the pulpous, vampish maîtresse de ballet, Rita Gilbert. And there was my half-sister, tall and masculine, who played bit-parts but threw her weight around, on account of her father. In fact, what I remember most about that occasion was her walking up to my father, sitting next to Nathan Katz - it was a Sunday evening - and crying, in French, loud enough to be heard by the whole room: “Don’t forget, Papa, that you haven’t been to church yet, today!” I remember distinctly that Nathan Katz was startled. My mother was horrified; I found it rather funny. She was probably miffed because Mama and I were sitting with the “big guys.”

Sometimes, as a kid, on my way to school, I would come across one or the other of these “Cercle” habitués on a sidewalk in Mulhouse, and they would acknowledge me, and smile, and greet me like an adult (even, once, the mayor!) and I would feel proud. For them, I was “Hortense’s little girl” (and maybe even, for some, Jules-Xavier’s...). After my father’s death, when I was 13, we did not return to the “Cercle” and I no longer had any occasion to meet Nathan Katz. I continued to read his weekly poem, until my mother was pushed out of her job and of the agency. Even, in my teens, I set a few of Katz’ poems to music. Namely, this one:

I ha di aber so gàrn!

Wie mànkmol z’nacht

Wenn dr Wing an dr Lade het gschlage,

Bi n i in Gedanke an di

Still unger de Zieche glàge.

I ha di jo so gàrn!

(...)

Decades later, I translated some poems by Nathan Katz into English for Al, and for our friends in New York, and even one or two, about the Swedes in the Sundgau during the Thirty Years War, for our Swedish friend, Peter Gillgren.

Reading Annele Balthasar, you may recognize some of the Alsatian tradition in which Nathan Katz is rooted:

The Tristan of Gottfried von Strassburg; Albert Schweizer; the Mystics: Meister Eckhart and Johannes Tauler; the Isenheim altarpiece; Hans Baldung-Grien; Madonna of the Rose Bower, of Martin Schongauer...

Addendum:

In March 2023, I visited Jean-Louis Spieser in Alsace, who is passionately engaged with Nathan Katz’ poetic legacy. He has discovered that the poet’s childhood friend, a student at the Altkirch teachers’ school, who initiated him to the great poets of the world’s cultures, was Alfons Becheln, a native of the neighboring village of Riespach. He was killed in battle in 1915 at Mittelkerke, near Ostend.