The Exact Date of the Deaths of Patroclus and Hector: Was It June 6th-7th, 1218 B.C.?

A new astronomical dating of the trojan war's end, by Stavros Papamarinopoulos

Go to the article in pdf

“The Anger sing, o Goddess, of Peleid Achilles...”

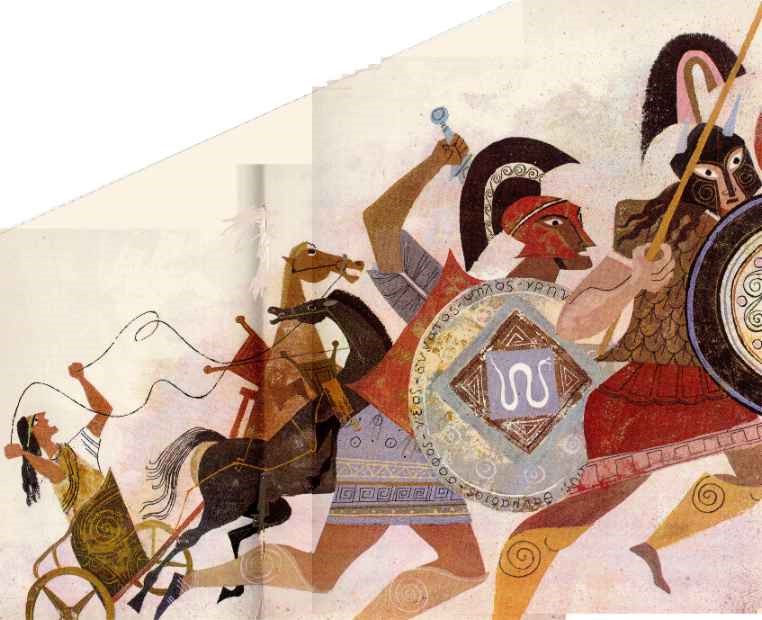

Thus begin Homer’s Iliad and Western literature. The Greek word “mênis,” signifying anger of a supra-human and baleful nature, harmful and destructive, strikes the initial chord, still resonating today, and any translation which puts this word in any other place than at the beginning of the first verse misses the point and the significance of Homer’s poem. This is an utterly strong and unauspicious beginning. Achilles’ anger, which structures the poem (and remains a narrative device of a never equalled power) enters into its phase of destructive, nova-like explosion in Book XVI, (also designated as the Patrokleia) when, in the face of the Trojan threat to the besieging Greeks’ ships and encampment, Achilles allows his intimate companion, Patroclus, to transgress his, Achilles’, anger-determined “walk-out” from the fighting, and to lead Achilles’ men into battle, clad in Achilles’ armor and carrying his weapons. Patroclus is killed by the combined blows of the god Apollo, the Trojan Euphorbus who delivers an injurious blow, and Hector himself, the leader of the Trojans, who finishes him off.

Before that, Patroclus had sealed his doom by killing in battle Sarpedon, a son of Zeus, leader of the Lycians, fighting on the side of the Trojans. Patroclus even fought back with unpious fierceness attempts made by Hector and the Lycians to retrieve Sarpedon’s divine body, exclaiming: “Sarpedon is fallen, he who was first to overleap the wall of the Achaeans; let us take the body and outrage it; let us strip the armour from his shoulders, and kill his comrades if they try to rescue his body." Sarpedon’s body was despoiled of its armor and weapons. The god Apollo, on Zeus’ order, had then spirited away the body and had washed it in the waters of the river Scamander, anointed it with ambrosia and clothed it in immortal garments, and left it in the care of the twin gods Hypnos (sleep) and Thanatos (death) to be carried off to his home in Lycia.

Apollo then turned on Patroclus: “Patroclus did not see him as he moved about in the crush, for he was enshrouded in thick darkness, and the god struck him from behind on his back and his broad shoulders with the flat of his hand, so that his eyes turned dizzy. Phoebus Apollo beat the helmet from off his head, and it rolled rattling off under the horses' feet, where its horse-hair plumes were all begrimed with dust and blood. Never indeed had that helmet fared so before, for it had served to protect the head and comely forehead of the godlike hero Achilles... The bronze-shod spear, so great and so strong, was broken in the hand of Patroclus, while his shield that covered him from head to foot fell to the ground as did also the band that held it, and Apollo undid the fastenings of his corslet. On this his mind became clouded; his limbs failed him, and he stood as one dazed...” Euphorbus, who is at hand, drives his pike into Patroclus’ back and runs back for cover into the ranks, “but Patroclus unnerved, alike by the blow the god had given him and by the spear-wound, drew back under cover of his men in fear for his life. Hector on this, seeing him to be wounded and giving ground, forced his way through the ranks, and when close up with him struck him in the lower part of the belly with a spear, driving the bronze point right through it, so that he fell heavily to the ground to the great sorrow of the Achaeans.”

Patroclus’ death brings Achilles’ “nêmis,” his anger, to an acme of revenge and the following day, he kills Hector. For eleven days after this, bereft of sleep, he will drag Hector’s body attached to his chariot through the dust every morning around Patroclus’ tomb. The Iliad ends on the twelfth day, when old King Priam, Hector’s father, secretly visits Achilles in his tent and begs him to surrender his son’s body in exchange for gifts. Achilles grants him his wish, as well as hospitality, and a twelve day truce to allow the Trojans to organize a fitting funeral for Hector.

In an article entitled The Exact Date of the Return of Odysseus to Ithaka: was it on October 25th to 30th, 1207 B.C.? and published on Q-Mag.org, Stavros Papamarinopoulos, of the University of Patras, harking back to a discussion with William Mullen and others around the dinner table at the Quantavolution Conference in Kandersteg, Switzerland, in June 2009, and taking into account the date of a solar eclipse already referred to by the astronomer Heraclides of Pontus, as well as the configuration of the heavens and the seasonal indications as mentioned in the homeric text, came up with said date for the return of Odysseus, October 30th marking the day of the killing of the Wooers. From this, could be deduced the all-important date of the fall of Troy, which occurred immediately following the death of Hector. Odysseus’ travels and travails between the end of the Trojan War and his Return to Ithaca having lasted ten years, this date had to occur some time between 1216-1218 B.C.

Starting from the fact, remarked upon by others before him, that a puzzling verse in Book XVI, which mentions the presence of both the Sun and Moon in the heaven around noon on the day of the battle, as well as the description of an evolving darkness on the battle-ground, coupled with an unusually bright sunlight above, seem to point to a partial eclipse of the sun lasting from the time of the death of Sarpedon to the time of Patroclus’ death, Prof. Papamarinopoulos was able to narrow the date to the only possible solar eclipse visible in the Near East during this period. It turned out to be an annular eclipse, and lo and behold, it occured in the early afternoon, which would make it coincide perfectly with the narrative of Sarpedon’s and Patroclus’ deaths.

As in the case of the date of Odysseus’ return to Ithaca, the configuration of heaven and the seasonal indications carried down in the homeric text also concur, further bolstering the case for Stavros Papamarinopoulos’ dating.

According to him, Patroclus would have been killed on June 6th, 1218 B.C. Hector would therefore have been killed on June 7th, the night of June 6th-7th having been put to use by the god Hephaistos to fashion new weapons for Achilles, in replacement for those lost with Patroclus, a magnificent shield picturing the cosmos in concentric layers, centered on Ouranos, Heaven, and surrounded by Okeanos, the Ocean; a cuirass, a helmet and a pair of cnemides (shin protections). Patroclus’ funeral takes place on June 8th, the visit of Priam to Achilles’ tent on June 19th, the retrieval of Hector’s body and the beginning of the preparation for his funeral on June 20th, which brings us to the close of the Iliad, making it coincide with the summer solstice... After that, the truce would presumably last until July 1st, which would put the fall of Troy, which is not told in the Iliad, at the beginning of July, 1218 B.C.

Papamarinopoulos’ hunch, already indicated in classical time, that histories transmitted by oral tradition would have been organized around common memories of solar eclipses, appears here perfectly credible.

Anne-Marie de Grazia

June 9th, 2014

The translations of the passages of Homer are Samuel Butler's. The illustrations by Alice and Martin Provensen stem from the iconic 1950s children book, The Iliad and the Odyssey, published by Simon and Schuster.

Go to article "A New Astronomical Dating of the Trojan War's End" in pdf.