Bon appétit! Neolithic Pigs roasts at Stonehenge - Paleolithic rabbit-snacks for Neanderthals

Archaeologists have unearthed new proof of the existence of early, large-scale, island wide celebrations in Great-Britain. It appears now that humans and animals covered hundreds of miles to take part in Neolithic ritual feasts. This is the conclusion arrived at by Dr Richard Madgwick, of the School of History, Archeology and Religion of the University of Cardiff, who has led research in collaboration with his colleagues of the University of Cardiff School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, and with the Earth sciences Isotopes laboratory of the NERC of the British Geological Survey of the University of Sheffield and of University College London and published in the magazine Science Advances.

Nowadays, over one million people from all over the world visit every year the site of Stonehenge, in the South of today’s England, surely the best known monument of the European stone age, it's late and crowning achievement. 4,500 years ago, when it was newly erected, it seems to have exerted just as powerful an attraction. At that time, humans from all parts of Britain congregated to a huge Winter festival, as revealed by an analysis of pig bones and pig teeth dating back to that time.

« At other periods, many herds of sheep and bovines were held in Britain, but for this period, we find mostly the bones of pigs, » explains Richard Madgwick, to justify the concentration of archaeological attention on these animals.

At a distance of merely 2,5 kilometers from Stonehenge, lies the deposit of Durrington Walls, in which scientists found, buried next to a stone circle, a large amount of animal bones. 90 percent of the bones came from pigs, a mere eight per cent from bovines, and there were practically no bones of sheep at all.

The isotopic record

For Richard Madgwick, whose main interest lies in determining the areas from which Neolithic humans came to gather at Stonehenge, this was not at first the best of news. Normally, he and his colleagues use so-called isotope analysis of the bones and teeth of humans found to have been buried in that area at said periods, in order to gather indications about the regions where the dead had lived - with the hope of finding some unfortunate visitors who had not made it back home. But as it happens, only few human neolithic bones have been found in Stonehenge.

As it is possible to drive herds of cattle and sheep over large distances, isotope-analysis of the remains of these animals can also yield information about their provenance as well as about the home of their owners. Whereas cattle herds were driven across the North American continent in the XIX century, for instance, similar mobilizations of domestic pigs are unknown.

„One could surmise therefore that peasant in these areas around Stonehenge raised and fattened pigs which they then sold to the visitors who came to the huge festivals, » says Madgwick. If this hypothesis were true, the bones of the pigs would hardly provide any indications about the mobility of the humans.

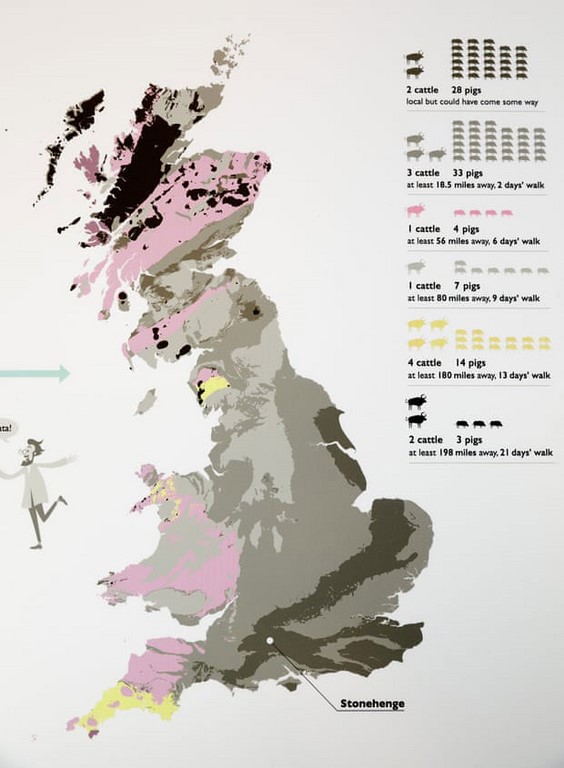

Together with Madgwick, Jane Evans and Angela Lamb of the British Geological Survey in Keyworth examined the bones of 131 pigs which 4,500 years ago had been buried at Durrington Walls and in three other sites isolated by earth walls in the vicinity of Stonehenge. Using five different elements and their isotopes: sulphur-34, which originates from chemical bonds released by marine organisms, which end up in the air by way of the sea-spray - this isotope indicates if an animal lived close to the coast or inland; Strontium-87 and Strontium-88 give an indication about the geological underground upon which the animal was living; whereas oxygen-18 gives indications about the climate; from carbon-13 und nitrogen-15, scientists can draw conclusions about the animals' diet.

Madgwick compared the combinations of these five isotopes with finds from all over Britain, which allowed him to determine relatively accurately the area from where the pigs originated. To his astonishment, he discovered that few of the pigs had actually lived in the vicinity of Stonehenge. Instead, they came from various areas in all corners of Britain.

Which raises the question of how the pigs came to Stonehenge. It is possible that Neolithic humans of 4,500 years ago slaughtered the animals at home and took only their meat with them on the trip. Pork meat spoiling fast, they might have preserved it thanks to salting or smoking, and have broken off for the far-off festival with savory hams in their packs.

« However, we are finding in Durrington Walls large quantities of pig skulls and jawbones, which hardly carry much meat, and the transport of which would not have been worth the trouble, “ thinks Richard Madgwick.

On the other hand, it is hardly likely that live pigs could have been driven overland from Scotland or Northern Britain to Stonehenge. Granted that pigs find plenty of food in Summer and that they can be driven into the forests in Fall to fill their bellies up with acorns. But they would not let themselves be driven like a herd of cattle all the way from there to Stonehenge.

"And if it were possible nevertheless, they would have arrived in a skinny state in Durrington Walls“, Madgwick is convinced of this.

That leaves transport over water. Achaeologists know that even on far-away islands such as the Orkneys in the North of Scotland, humans used the same ceramics as on the mainland. There must have been boats and ships. On these, it is easy to transport pigs. From inland, one would have gone down rivers to the North Sea or the Irish Sea, then follow the coast to the English Channel. From there, the men would haul the boats up the river Avon and would reach Durrington Walls and Stonehenge a few weeks after their departure, in time for the big Winter solstice festival.

Roland Knauer

(partial article in Stuttgarter Zeitung)

Translated by Anne-Marie de Grazia

Go the Stuttgarter Zeitung original article.

In the Paleolithic: Pre-Neanderthal and Neanderthal rabbit snacks

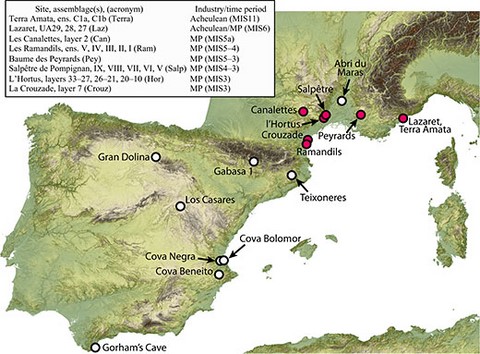

A French-Canadian study of various deposits dating from -400,000 to -40,000 years reveals the presence of large numbers of rabbit bones.

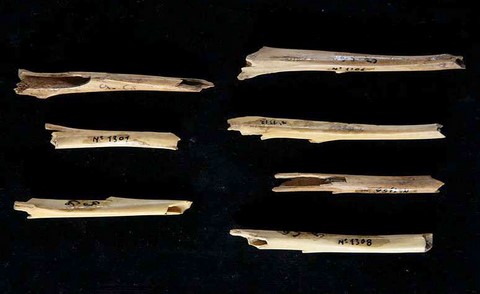

Rabbits, being lightweight and fast, are hard to hunt and yield only a small amount of meat. A study published by anthropologist Eugene Morin (Trent University at Peterborough, Ontario) in the magazine Science Advances, shows that rabbits figured on the diet of the early humans and of the Neanderthals of Southwest Europe, as early as 400,000 years ago.

Prof. Morin and zoo-archaeologist Jacqueline Meier (University of North Florida) examined the fossil remains of fauna from eight French paleolithic sites, notably the site of Terra Amata and the cave of Lazaret, in the area of Nice, on the Mediterranean coast. Terra Amata is one of the oldest sites known in Eurasia where Homo left traces of his hunting activities.

According to Prof. Morin :

"Big game, like horse, bison and deer made up most of the meat-based diet, but it is likely that, in the Northwest area of the Mediterranean, animals which were more difficult to catch, like rabbits, may have contributed in filling the gaps when it came to food supplies (for instance, during migrations). » Small game hunting could have been an effective strategie to supply the group with food resources which were necessary for its survival.

On many French sites, researchers have found cracked-up rabbit bones. They also did some « digging » in museum reserves. Elements and bones found in already investigated and closed deposits are preserved in museums for the sake of later research. The scientists arrived at the conclusion that small rabbit bones were very often to be found buried in prehistoric deposits.

"Many of these ancient Neanderthal sites yielded up to 80 to 90% of rabbit bones", states Eugene Morin. "It was nothing rare."

This is something which other predators, such as wolves and hyenas, do not do. As for the signs of burning, they indicate the existence of fire, necessarily kept up by hominids."It looks like the early humans broke off the extemities with their teetch in order to fashion a kind of tube from which to suck easily the calories-rich marrow. "

Hunting for rabbit, or for small game, does not require the same competences nor does it present the same risks as the hunting of mammoths or bison. Small game can be caught by a single individual, whereas a large animal requires mobilizing several hunters. In order to kill a large animal, one needs to be equiped with stakes, speers and other weapons which can be thrown or thrust to wound the animal. To catch small game, the first Europeans probably devised crude traps, tricks, and snares …

Prof. Morin’s research calls into question the general consensus that small game hunting in Europe started some 40,000 years ago, with Homo sapiens. His team's work shows that even in the early Paleolithic, hominids consumed other meat besides the large mammals which constituted the major part of their caloric intake. This discovery is also important as it shows that the early Europeans were able to broaden their diet in cases of food shortages, a type of behavior which had been thought until now to be proper to modern man.

Not all the sites studied have yielded hominid remains. The period studied, between 400,000 and 40,000 years, leaves only one kind of hominid present in that area: Neanderthal or pre-Neanderthal. The stone tools found on site belong to Neanderthal lithic cultures.

The first Europeans are often presented has having been big game hunters, tracking mammoths, deer and wooly rhinoceroses. We must now add rabbits to their shopping list !

Anthropologist Julien Riel-Salvatore (University of Montreal) states that:

« Neanderthals as it were, were capable to hunt small, fast little animals, which had been considered up to now the cornerstone for the growth and resilience of modern humans when they arrived in Europe, 45,000 years ago. »

He adds that this required a know-how and abilities which were clearly distinct from those needed to fashion hunting tools…

Translated from the French and slightly adapted by Anne-Marie de Grazia

Go to the original article on the Hominidés website (March 12, 2019)

Go to the original article (in english) in Science Advances (March 6, 2019)

My great-grandmother, heir to a very old tradition...

Come Summer and grain-harvest time, my Alsatian great-grandmother, Catherine née Gerspacher, born in 1851, would take a day off from her husband and children (she had 13 of them) to walk over to the German side of the Rhine, to the village of Bamlach, near Kandern, in the duchy of Baden, to help her relatives bring in the harvest. She would break off alone before dawn, cross the Hardt forest – an alluvial forest, about seven kilometers deep at that point – then, gathering up her numerous skirts, wade through the broad ford of the Rhine. The trip on foot amounted to about thirteen kilometers, one way, which would no longer be possible today, as one would have to drive some 35 kilometers to cross a bridge over the Canal of Alsace and the straightened Rhine river. While crossing the forest at dawn, she would set snares along her way and, returning home in the evening, after a healthy day of work in the fields, she would visit her traps and pick up the hares which had been caught. She would hang them around her waist, under her skirts, and walk home, tired and heavy with poached hares - an adult hare in Summer easily reaches a weight of 5 kilos… She would prepare them as Hasenpfeffer, marinating them in red wine, shallots and juniper bays. She did this faithfully into her old age, and even my mother, the child of her youngest son, remembered being put in charge of carrying home to her parents pots of this yearly delicacy. Catherine died in 1941, age 91.

Anne-Marie de Grazia