Stars in Collision

"Nova 1670 Vulpecula" was not a nova

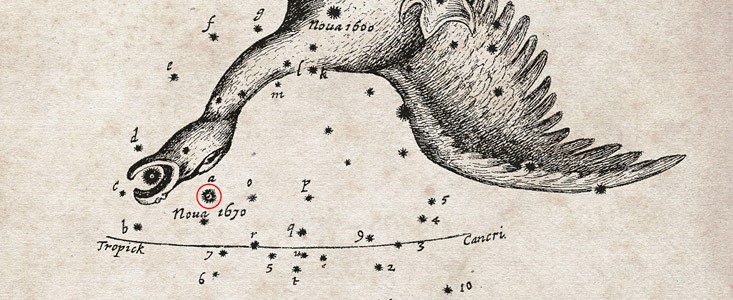

The Nova of 1670 as recorded by Hevelius "below the head of the Swan." It was later listed as part of "Vulpecula," the Little Fox, as "Nova 1670 Vulpecula."

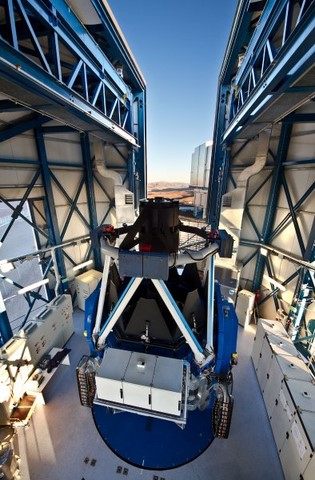

In 1670, astronomers in Europe saw a “new” star shining. It was long surmised to have been a usual nova. With the help of the APEX-Telescope in Chile, operated by Eso (European Southern Observatory), of the 100m-radiotelescope at Effelsberg and the cooperation of other observatories, scientists of Max-Planck-Institute of Radioastronomy in Bonn have discovered that it originated in a much rarer event of a massive and cataclysmic collision between two stars. The original explosion in 1670 was so powerful that it could be easily observed by the unaided human eye. Yet the remnant traces are presently so weak that a very careful analysis of observations using submillimetre telescopes was necessary for the enigme to be solved, after 340 years. The results appeared on March 23, 2015 in the online publication of the magazine Nature: "Nuclear Ashes and outflow in the eruptive star Vul 1670."

This “new star” in the constellation Vulpecula was discovered by Père Dom Voiture Anthelme (ca. 1618 - Dec 14, 1683), a Carthusian monk in Dijon, France, on June 20, 1670. He discovered it as a star of about 3rd magnitude. It was independently noted by Johannes Hevelius (1611 - 1689) from Danzig on July 25, 1670. The star faded from visibility until October, 1670, but had a second maximum in 1671, when again Anthelme recovered it on March 17. It reached about mag 2.6 on or about April 30, 1671, and was observed by Hevelius and Giovanni Cassini through late spring and summer of that year until it faded from naked-eye view in late August. Hevelius found it again brightening in March 1672, and could observe it until May 22, 1672, but that year it was just hardly observable (mag 5.5 to 6) and did not brighten again to its previous brilliance. Unfortunately, besides some very detailed brightness observations, little is recorded of this phenomenon, especially no hint to its color appearance.

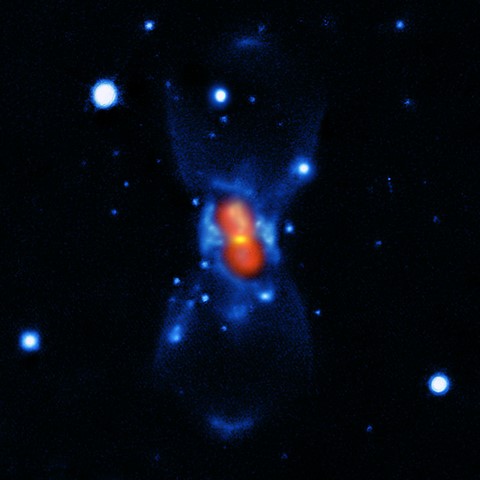

The remnants were found by Shara and Moffat in 1982 (also Shara, Moffat, and Webbink 1985), 312 years after its historic outburst. They found that associated with a central object, there are two nebulous blobs radiating mostly in H Alpha and [N II] lines, and derive a distance of about 550 +/- 150 pc, standing in or behind an obscurring cloud of interstellar matter. Formerly, Milton Humason in 1938 had looked in vain for this remnant on the blue POSS photographic plates.

Hevelius, the father of Moon cartography, left careful recordings of the new star, which he described as Nova sub capite Cygni – as a new star below the head of Cygnus, but it is known to astronomers today as Nova Vul 1670 [1]. Historical descriptions of nova eruption are rare and of great interest for modern astronomy. Nova Vul 1670 is considered both as the oldest Nova recorded as such, as well as the faintest when its remnants were rediscovered at a later time.

The lead author of the new study, Tomasz Kamiński (ESO and the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy, Bonn, Germany) explains: “For many years this object was thought to be a nova, but the more it was studied the less it looked like an ordinary nova — or indeed any other kind of exploding star.”

When it first appeared, Nova Vul 1670 was easily visible with the naked eye and varied in brightness over the course of two years. It then disappeared and reappeared twice before vanishing for good. Although well documented for its time, the intrepid astronomers of the day lacked the equipment needed to solve the riddle of the apparent nova’s peculiar performance.

During the twentieth century, astronomers came to understand that most novae could be explained by the runaway explosive behaviour of close binary stars. But Nova Vul 1670 did not fit this model well at all and remained a mystery.

Even with ever-increasing telescopic power, the event was believed for a long time to have left no trace, and it was not until the 1980s that a team of astronomers detected a faint nebula surrounding the suspected location of what was left of the star. While these observations offered a tantalising link to the sighting of 1670, they failed to shed any new light on the true nature of the event witnessed over the skies of Europe over three hundred years ago.

Vul 1670 as "seen" by Eso telescope

Tomasz Kamiński continues the story: “We have now probed the area with submillimetre and radio wavelengths. We have found that the surroundings of the remnant are bathed in a cool gas rich in molecules, with a very unusual chemical composition.”

As well as APEX, the team also used the Submillimeter Array (SMA) and the Effelsberg radio telescope to discover the chemical composition and measure the ratios of different isotopes in the gas. Together, this created an extremely detailed account of the makeup of the area, which allowed an evaluation of where this material might have come from.

What the team discovered was that the mass of the cool material was too great to be the product of a nova explosion, and in addition the isotope ratios the team measured around Nova Vul 1670 were different to those expected from a nova. But if it wasn’t a nova, then what was it?

The answer is a spectacular collision between two stars, more brilliant than a nova, but less so than a supernova, which produces something called a red transient. These are a very rare events in which stars explode due to a merger with another star, spewing material from the stellar interiors into space, eventually leaving behind only a faint remnant embedded in a cool environment, rich in molecules and dust. This newly recognised class of eruptive stars fits the profile of Nova Vul 1670 almost exactly.

Co-author Karl Menten (Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy, Bonn, Germany) concludes: “This kind of discovery is the most fun: something that is completely unexpected!”

Eso telescope in Chile

Sources:

Eso communication plus addition from Der Spiegel and Hartmut Frommert and Christine Kronberg.

(AMdeG)