Neanderthal - the painter and installation artist

Uranium-thorium dating has recently yielded sensational and far-reaching returns in the domain of palaeontology. It has totally upset the dating of some early artifacts found in Europe, assigning their creation to the Neanderthals instead as to Homo Sapiens. Such has been the case of the cave assemblage of Bruniquel, in France, to which was assigned, in 2016, the mind-boggling age of 176,500 years, give or take 2,100... followed, only recently, to a dating to 65,000 years found for some cave paintings in Spain, ante-dating by at least 15,000 years the arrival of the first Homo Sapiens coming out of Africa...

The Bruniquel Cave

What with the bulging arches of his eye-brows, his beettle-brow and huge nose, Neanderthal man really didn’t look like he might have been a rocket scientist... For a long time, the scientific community even took this short, stocky and musclebound human for some kind of a prehistoric retard. [It was even suggested that he should be named homo stupidus. n. of the ed.] A pure case of hasty judgement and discrimination on grounds of looks! For a few years now, thanks to new discoveries, palaeontologists have been re-evaluating Neanderthal man. Our cousin mastered fire, knew admirably to hew silex stones, probably used language and buried his dead* and… he built bizarre contraptions deep inside caves !

This is the new major discovery published this Thursday, May 26 [2016], in the scientific magazine Nature. In the cave of Bruniquel (France, department ofTarn-et-Garonne), a French-Belgian team discovered a strange circular structure made out of 400 pieces of stalagmites, in two concentric circles, weighing 2.2 tons in toto, and aged 176,500 years ! Much, much older therefore than the most ancient proof of a human presence in caves : the 38,000 years old painted Chauvet cave in the French department of Ardèche. Enough to feed a debate about the cognitive abilities of the Neanderthals.!

The story begins in 1990, when a young speleologist discovers the cave, a sub-terranean splendor dotted with lakes, floating calcite, translucid draperies, concretions of all kinds. The first crew to enter this space out-of-time noticed the presence of bone remains from animals of the Pleistocene (reindeers, bears, bisons), bears' nests and traces of clawing... Then, 336 meters from the entrance, they fall onto a funny heap of stalamites which seem to form a circle. All around this circular shape, the speleologists notice calcinated bones, calcite reddened by exposure to the flame: the rests of fires. Who lit those ? When ? And this structure : was it natural or man-made ?

In 1995, a first team of researchers determines, from a burnt bone found on the spot, and thanks to the Carbon 14 dating technique, that the fires go back 47,600 years: which means only that the datation limit of carbon 14 has been reached. And then, curiously, the cave was left to itself. [See below: Interview of Sophie Verheyden]

We’ll have to wait for another archaeological campaign, launched in 2013, to take us much, much farther. Thanks to a 3D plotting of the structures and an inventory of the exact position of the stalagmites, the team, made up of Dominique Genty, a director of research at the French Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Jacques Jaubert, professor of prehistory at the University of Bordeaux, and Sophie Verheyden, a researcher at the Royal Institute of Natural Sciences of Belgium, prove the anthropic origin of this construction, which stretches over 29 square meters: the stalagmites have been cut and displaced, they have been arranged and perfectly calibrated; some structures are juxtaposed or superposed over four layers or rows, one even finds wedges propping up the construction. Nature doesn’t put up wedges! Therefore it was man, the culprit! As for the burnt vestiges, spread over 18 fire holes, their they are witness to the presence of fires, to provide light for the workers!

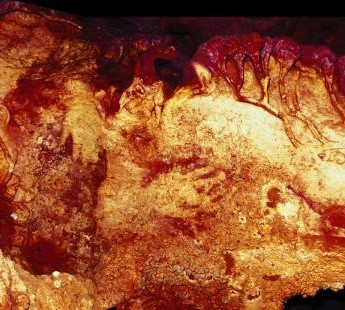

That man should invest himself in caves is nothing new, even if it is quite rare. At the beginning of the late Palaeolithic, in Europe, in Asia and Oceania, some courageous souls ventured underground, far from the light of day. They left behind drawings or engravings, such as at Chauvet, Lascaux (-22,000 years), Altamira in Spain (-18,000 to -15,000 years). But structures such as the ones at Bruniquel ? Such have practically never been found. And it’s always modern man who puts his signature on everything that is ever discovered.

The formidable discovery is owed to the Belgian Sophie Verheyden, a stalagmites specialist, who,while inspecting the famous structure, decided to take some well-chosen samples (at the end of the cut-off stalagmites and at the base of the embryos of stalagmites which formed after the construction) in order to precisely date the construction with the method called Uranium-Thorium, uranium decaying into thorium in stalagmites. The verdict fell : -176,500 years ! It wasn’t Homo Sapiens who was involved, this time, but the Neanderthals! When Jacques Jaubert, a Neanderthal specialist, got the news, he was flabbergased :

« Before seeing these results, I would never have imagined that Neanderthals were capable of venturing so deep inside a cave ! »

Bolstered by this incredible discovery, Sophie Verheyden, Jacques Jaubert et Dominique Genty will now try to solve the big question : what could have been the purpose of such structure? Was it a cultic place? a picnic area for roast bear eaters? a protection against the cold during the ice age ? And why go so far inside the cave ? Questions accumulate over the head of the Neanderthal, not so beetle-browed after all!

Nicolas Delesalle

translated from the French by Anne-Marie de Grazia

* with flowers, as is an burial site in Irak; and even carefully burying a stillborn foetus, as in La-Chapelle-aux-Saints (department of Corrèze)...

An interview of Sophie Verheyden

«When I entered the great hall of the cave of Bruniquel, I was first struck by its beauty. The concretions are superb, as well as the succession of basins, each one full of crystal-clear water. The colors, too, are magnificent, ochre, yellow, orange, » reminisces Sophie Verheyden. Having overcome her first emotion, the 44 year-old Belgian science doctor and geologist gets closer to the cut-off stalagmites disposed on the floor. It is for their sake that she wanted to explore this cave of the Aveyron river gorges, in Tarn-et-Garonne. The year before, in 2008, while on vacation in the area, Sophie Verheyden had spotted them on a photograph on display in a small exhibition at the Château of Bruniquel. She had been struck by their strangeness. She had contacted the local speleological club and learned that the cave, which is close to the castle, had been explored for the first time in 1990 by a team of speleologists and that an archaeological study had been carried out in 1995. A burnt bone had been analyzed and dated at at least 50,000 years, at the limit of the dating technique of Carbon 14. But since then, the cave had fallen into oblivion.

This was all that Verheyden needed to decide to restart scientific investigations. She knew that thanks to the uranium-thorium dating method she had the means to date the construction made with the broken concretions. It must logically have happened between the end of the growth of the broken-off stalagmites and the base of the stalagmites which grew on top of these same broken concretions. She also was an expert in the matter. Is she not a specialist in environmental and climatic reconstruction based on the study of stalagmites ? In order to carry out her project, she decided to associate herself with specialists and contacted the archaeologist Jacques Jaubert. Together, they filed a research request with the archaeological department of the area and, in 2013, they started a first research campaign consisting in observing and measuring every piece of the structure – exactly 399 of them ! The following year, they proceeded to coring some of the cut stalagmites.

« We don't know how the stalagmites have been cut. We haven’t found any piece of wood, not even any traces of impact, » she states.

The samples are brought to Brussels where, in the labs of the Royal Institute, Sophie Verheyden undertakes some cutting and polishing before sending them to Minnesota to be dated.

«When I received the charts with the results and understood that the stalagmites had been laid down in such a far-off time – we were hoping for -80.000 or -90.000 but not for -176.500 ! – I couldn’t believe them. I re-verified my samples, redid my analyses, and arrived at the same results as before. These concretions were indeed deposited on the floor of the cave 176,500 years ago ! The news immediately appeared unimaginable to us for, at that time, these regions of France were inhabited only by Neanderthal man et nobody would ever have thought that they could have made such constructions. »

A beautiful and just consecration for this scientist who has been able to ally her work and her passion for speleology. Since childhood, Sophie Verheyden has been visiting caves in all corners of the world, in Belgium as well as in Mexico and Vietnam. This passion, which she inherited from her parents, shares with her husband and transmitted to her daughters, lead her to study geology at the Free University of Brussels, to make her doctorate on stalagmites and take on scientific projects with various institutions and universities, resulting in the successes we know.

« Underground, I feel good ; everything is quiet there, removed from the day-to- day and from stress. One has time to think and to reflect on existential questions. Speleology is also a human adventure which one carries out together with others and during which one shows oneself as one is. It's hard to fake when one finds oneself in a difficult environment, reputedly hostile, where it’s dark and cold. Everybody there is genuine, » concludes Sophie Verheyden.

Le Soir, Brussels, June 21, 2016

Interview by J.S.

Translated from the French by Anne-Marie de Grazia

Neanderthal cave-paintings in Spain

Long before early modern humans arrived in Europe, Neanderthals were painting in caves, leaving behind animal shapes and hand-prints. This indicates that the stereotype of the brutish Neanderthal is wrong — they were cognitively closer to us than many think.

We often think of art and culture as exclusively the domain of humans — specifically our particular species, Homo sapiens. But the more we learn about other early hominid species, the more it seems that idea may be wrong.

Long before what researchers refer to as "modern" humans ever reached Europe, our Neanderthal cousins were creating cultural objects and painting in caves in Spain, according to several recently published studies. The new research has pinpointed when some of the first European art that we know of was created.

According to the scientists, the earliest cave paintings in Spain (from three different sites) date back more than 64,000 years. These paintings are red and black in color and depict geometric shapes, hand-prints, hand stencils, and even animals like horses, deer, and birds.

The paintings were dated using a technique called uranium-thorium dating, which is far more precise for estimating the dates of such creations than the radiocarbon-dating method that was used in the past.

"This is an incredibly exciting discovery which suggests Neanderthals were much more sophisticated than is popularly believed," archaeologist Chris Standish of the University of Southampton, one of the two lead authors on the paper, said in a news release.

Homo sapiens first evolved approximately 200,000 years ago. Some early groups of human ancestors likely first left Africa as far back as 120,000 years ago, according to recent research. But the bigger migration from the birthplace of humanity didn't begin until 60,000 years ago — and it took some time before populations settled in Europe.

Neanderthals were around long before those first modern humans, however. They first appear in the fossil record about 400,000 years ago, then disappear about 40,000 years ago. Many researchers have assumed those Homo neanderthalis were far more primitive than their later-evolving relatives. But these new discoveries challenge that line of thinking.

Scientists and archaeologists have found that Homo sapiens engaged in creative and symbolic behavior going back at least as far as the Spanish cave paintings do. According to the new studies, decorative artifacts dating back 70,000 and even 92,000 years have been found in Africa.

But there's long been a debate about whether Homo sapiens were the only species capable of thinking this way and engaging in this sort of behavior. The latest studies suggest they were not.

"According to our new data Neanderthals and modern humans shared symbolic thinking and must have been cognitively indistinguishable," Joao Zilhao, team member from the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies in Barcelona, said in a news release.

"On our search for the origins of language and advanced human cognition we must therefore look much farther back in time, more than half a million years ago, to the common ancestor of Neanderthals and modern humans."

Questions about whether Neanderthals were cognitively on the same level as early modern humans will remain controversial. But this at least helps demonstrate that the brutish stereotypes we now associate with the word "Neanderthal" might be incorrect.

If Neanderthals were responsible for what we now think of as the first art ever created in Europe, then modern humans — Homo sapiens — are not so unique after all.

From The National Geographic: on Uranium-Thorium dating

...Some researchers had been reluctant, though, to say that Neanderthals could make symbolic art. Based on the evidence at the time, it seemed that early European art didn't flourish until a major wave of modern Homo sapiens arrived on the continent about 40,000 to 50,000 years ago.

Other studies did complicate the narrative. In France, scientists found jewelry made by Neanderthals around 43,000 years ago. In one Spanish cave, similarly ancient charcoal lies alongside cave paintings. But none of these sites substantially predated H. sapiens's arrival, leaving the door open to the idea that Neanderthals merely copied their new, more cultured neighbors.

“If you were to get a hundred representative archaeologists and ask them whether Neanderthals painted caves, 90 percent of them would say no,” says study coauthor Alistair Pike, an archaeologist at the University of Southampton.

To show that Neanderthals were artists, researchers would need to find art in Europe made well before 50,000 years ago. Pike and Zilhão started brainstorming how to do this in 2003, when they serendipitously met Dirk Hoffmann, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology who specializes in dating minerals.

Hoffmann's work relies on the fact that the radioactive element uranium dissolves in water, but the element thorium doesn't. When water percolates through soils into a cave, the waterborne uranium gets trapped in mineral crusts and radioactively decays at a predictable pace into thorium. Since scientists can be confident that no other thorium entered the crusts, measuring the relative amounts of uranium and thorium in minerals can reveal their ages, and thus the ages of any paintings underlying the rock.

To make this measurement, all Hoffmann needs is a bit of rock no bigger than a grain of rice. But getting those samples is no small feat, requiring the use of scalpels mere millimeters away from priceless art.

“One wrong move, and you might remove some pigments from the wall that were there for thousands and thousands of years,” says Hoffmann, the lead author of both studies. “There's this overwhelming feeling you get when you first get in.”

In the three caves with paintings, researchers found that some mineral crusts overlying the paintings were at least 64,800 years old, making the art itself at least that old, if not older.

Read the full article on the discovery of the Neanderthal paintings in National Geographic Magazine