The Salon Noir & the Cave of Niaux

At the turn of the year (2017/2018), we took a tour to the French Pyrénées, to the département of Ariège, which boasts stunning Paleolithic sites, and visited the Magdalenian Cave of Niaux, one of the few prehistoric painted caves in France which are still accessible to the public. Others, such as Lascaux and the Cave Chauvet, are closed, but visible in the form of very carefully executed fac-simile, which are well worth a visit. The Cave of Niaux, or rather, its main part, the Salon Noir, which is the only part that is accessible to the public, also exists as a fac-simile (and should be visited, as copies of elements which are not part of the guided tour can be seen there), inside a prehistoric theme park for adults and children, situated close-by. Most others, being extremely fragile environments, are entirely closed and can be known only from photos and videos. The Cave, or "Grotte" of Niaux, the real thing, can be visited upon appointment, easily made on Internet. Visitors are limited to groups of 20/25. There are 3 to 10 groups allowed per day, according to the season.

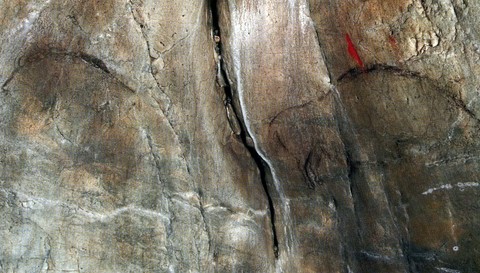

The cave of Niaux is one of the many cavities hollowing out the mountains of Cap de la Lesse, around the valley of the river Vicdessos, on the French side of the Eastern Pyrénées. It is situated some 15km to the South of the city of Foix, a hundred meters above the village of Niaux. On approaching, one discovers a gigantic rock porch (55m high and 50 m wide) into which a touristic pavillion has been tucked, preceded by a stately sculpture by Massimiliano Furkas, and where one may conveniently leave one’s car…

In contrast with the Cave of La Vache, on the opposite slope, the Cave of Niaux was never used as a prehistoric encampment, or dwelling. It is considered to have been a kind of a sanctuary, where prehistoric humans would have come only in order to look at, or to execute, paintings.

Its sheer size and proximity to the village make that the inhabitants of the area have always known of the cave's existence. One can find on the walls many historic graffitis made by travelers eager to leave a trace of their passage. The oldest is dated 1602… Another one casts blame upon the authorities: “this cave has been ravaged in 1820,” referring to the damage inflicted when stalactites and stalagmites were sawed off and sold wide and far to make fake romantic garden grottoes. The parts of the cave close to the entrance served as refuges, and sites of parties, political meetings, and lovers' trysts all through the 18th and 19th century.

It is only in 1866 that the prehistorian Felix Garrigou notices, eight hundred meters inside the cave, some wall paintings. He makes a note: “A large, round hall with funny drawings. What can this be? Amateur artists who have painted some animals. Why? Things already seen somewhere.” These remarks will be dismissed, including by Garrigou himself.

In 1906, the prehistorian Emile Carthailac, from the University of Toulouse, writes in the following terms about the circumstances of the (re-)discovery, or "invention," of the cave:

“On September 24, I was informed by my old friend Dr Garrigou that his neighbor in the countryside, Major Malard, had glimpsed some animal drawings inside a vast cave situated in the commune of Niaux. These gentlemen advised me to go ascertain the value of the fact and I immediately gave in to their advice. On the 28, most amiably guided by Major Malard and his sons, I went inside the cavern.”

Together with the archaeologist and anthropologist Abbé Henri Breuil, a Jesuit, then not yet thirty years old, who would come to be called the "Pope of Prehistory,” Emile Cartailhac went on to study the drawings and published the results in 1908 in his review L'Anthropologie.

The cave was classified as a historic monument on July 13, 1911.

We notice that, either Garrigou did not mention that he himself had already seen the paintings 40 years earlier, or Cartailhac did not care to take down the fact. Had Garrigou followed up on what he had stumbled upon, the Cave of Niaux might have been the first prehistoric painted cave ever discovered - or recognized as such.

This honor fell to the Cave of Altamira, near the Cantabric Coast of Spain. It was discovered in 1879, by a jurist and amateur archaeologist named Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola, the owner of the land on which the cave was situated; or rather, by his eight-year old daughter Maria whom he had taken inside the cave, where he had already spotted some geometric signs. The girl exclaimed that there were "toros" (bulls) on the ceiling! Sautuola realized that the pictures bore similarities with the engravings on small palaeolithic objects which he had had the occasion to see at the Universal Exposition in Paris the year before. The hypothesis of the paintings in the cave being prehistoric was adamantly rejected for over two decades by none other than the aforementioned Emile Cartailhac. Sautuola and a professor of the University of Madrid, Juan de Vilanova y Piera, who had authenticated the paintings, were publicly ridiculed at a 1880 Prehistoric Conference in Lisbon, and Sautuola was accused of forgery.

The discovery, in 1901, of the cave paintings at Font-de-Gaume, in the French region of Perigord, with some 180 paintings and carvings of animals, produced the effect, according to Abbé Breuil who was one of its co-discoverers, of

"an enormous petard in the world of prehistory,"

and made Cartailhac's position about Altamira untenable. He apologized in an article called: Mea Culpa: confession of a skeptic, confessing that he had not cared to look at the evidence seriously. Sautuola was by then fourteen years dead.

In 1970, in the Caves of Niaux, new galleries were discovered and explored: they form the so-called Clastres network. They had been protected from visitors for millennia, because they were only accessible after crossing four successive underground lakes. There too, drawings were discovered.

The Salon Noir

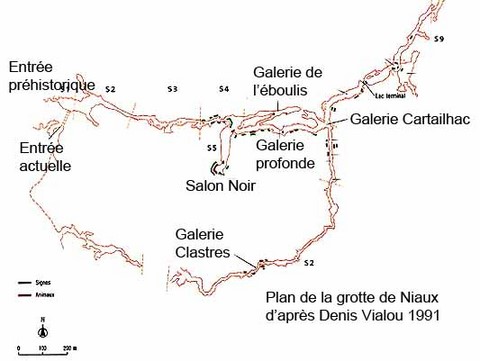

The Cave of Niaux is constituted by a network of several kilometers of galleries, of enormously varying dimensions: they go from little "catgut" like passages (in the Clastres network) to cathedral-like loftiness (such as the Salon Noir). The « visible » part of the cave is relatively easy of access and can be handled by most visitors: it suffices to negotiate some 800 meters of an uneven and slippery floor by torchlight to reach the Salon Noir. As for the Clastres network, it is situated some 2,000 meters from the entrance and is accessible only to the pros, with special authorization: they can expect partial inundations, ceilings so low that one must crawl on on's belly, descends through extremely narrow passages…

It must be noted that in prehistoric times, the Magdalenians did not use the gigantic porch which serves as the present entrance but a much more modest opening (1.6m high, 1.45 wide) which was 150m farther away and was reached through the past centuries with the help of ladders. A passage was opened much later, in historic times, from the large porch. These mountains are hollowed out by an inextricable network of caves, communicating through chimneys and kilometers of narrow passages. The Cave of Niaux even communicates with the grandiose Cave of Lombrives, billed as the largest in Europe, and much worth a visit, although not graced with any painting by Palaeolithic human. Actually there exists an even larger one within the same mountain system, quite inaccessible, said to be large enough to contain Notre Dame of Paris in all its dimensions.

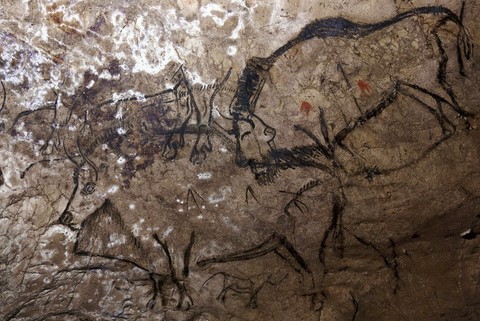

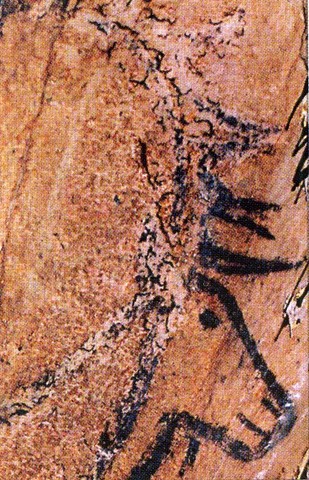

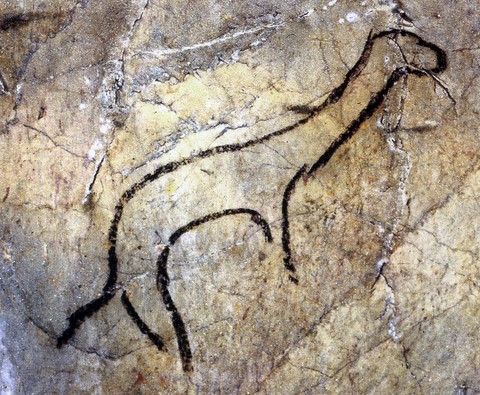

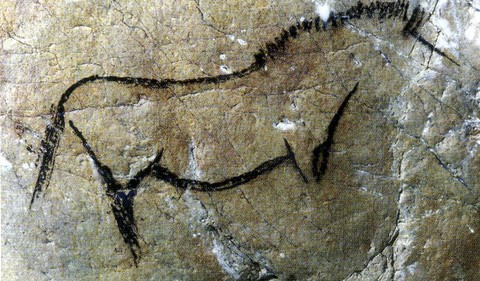

The cave of Niaux contains well over 100 figures and representations. There are at least 29 horses, 52 bisons, 3 other bovids, 15 caprines (ibexes), 2 cervids, 2 fish, 2 anthropomorphs, and 300 hundred groups of signs, mainly dots and lines. Whereas the majority of animal representations is to be found in the Salon Noir, the signs are positioned in the galleries and at important crossings.

On the walls, a few minutes after entering the cave, the first of these signs appear. They are dots, lines and key-shaped signs (claviforms) pointing either left or right (like q and p). Sixteen of these claviforms have been found in the cave to date. The signs were probably made with the fingers and using two colors: red and black. Chemical analysis of the signs reveals the use of manganese and wood coal from a resin tree, mixed with a binding material, such as oil. Twenty-seven animals are associated with signs.

To the right, there is an ornated panel made up of these signs, called « sign posts » by Henri Breuil who saw in them markers used by « the courageous explorers of the age of the reindeer. » The meaning of the signs remains mysterious. (I confess that I found the signs to be an almost as shattering an experience as the paintings ...)

In the Salon Noir itself, one finds 39 bisons on the walls and 8 on the floor, 9 ibexes on the walls and three on the floor, 19 horses on the walls and 4 on the floor, 2 reindeers on the wall and 4 anthropomorphs on the floor.

The Salon Noir contains more than 80% of the animals figured in the Cave of Niaux. All the representations show animals drawn in profile, executed with several black strokes, with a stunning attention to detail. These “artists of the past” would have come into this deep cave probably equiped with grease lamps or resin torches, having memorized an animal in order to draw it. (They could also, I think, have brought with them smaller engravings on portable objects, which we know well from the Magdalenian civilization, or even preliminary sketches.)

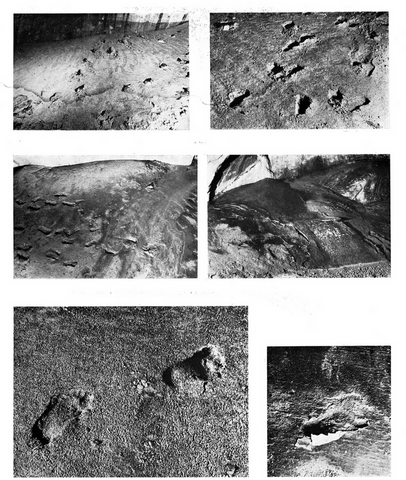

There are engravings on the floor, a prehistoric art technique which is exceedingly rare, either because not many suitable floors were available, or because most of them have been erased with time, or by mistake. Indeed, some engravings which have been described in the recent past, have now disappeared. It is possible that researchers, not expecting to find anything on the floor, simply erased them by walking on them.

The vast cavity, 45m high and shaped like a nave, has exceptional acoustic qualities. The least murmur or noise is repeated and amplified as an echo. "It is the only part of the cave which 'answers back,'" according to parietal art expert Jean Clottes.This may have been one of the reasons why the Magdalenians chose it as a site for painting.

The paintings were made over a period of about 1,000 years, according to Carbon 14 dating. Those of the main panel have been dated between 12,890 to 13,060 BC and one bison has been dated at 13,850 BC.

The Clastres network

The Clastres network, now accessible by crossing the lakes, seems to have been, during the Palaeolithic, distinct from the cave of Niaux. It is quite possible that its ancient access has been obstructed by the formation of a thick stalagmitic flow, rather recent in appearance. There are four lakes, the fourth of them opening onto a highly vaulted hall adorned with paintings, among them, the famous weasel - the unique occurrence of this animal in prehistoric art to date - done in ten secure strokes with a brush or charcoal, capturing a very "live" and characteristic attitude of the animal. This hall of paintings contains also a horse and three bisons, as well as four black lines and one red one.

A sandy embankment some 4m wide on the side of the painted hall of the Clastres network contains one of the most moving remains, the tracks of three barefoot children age 8 to 10, moving together at a quiet pace from the depth of the galleries towards the exit, then stopping and moving along very carefully, two of them clinging to the side, the other crossing the embankment diagonally. Remember that the place was stock-dark and that not a step could have been taken without the light of at least one torch. The tracks of the children can be followed beyond, in an area covered by calcite, where tracks of an adult going in the opposite direction are also found (it is not known if they were contemporary), then the tracks get lost because of the nature of terrain. Many more human tracks have been found all over the Clastres nework, numbering at least 500 and often superimposed. Moreover, some Paleolithic humans have intentionally traced long lines with their spread out fingers in the mond-milch (See Q-MAG: Palaeolithic hands) while walking along the walls. Remarkably, in practically all prehistoric caves in France where human footprints have been found, footprints of children are also present.

A great number of pieces of charcoal, left-over from torches, are found disseminated within the galleries of the Clastres network. Their C14 datation seems to show that human incursions in these parts of the cave of a very difficult access were limited to three or four passages. The oldest, dated to 11,000 BC to 10,000 BC, corresponds to the paintings. Another takes place around 8,000 BC, another around 5,500 BC, and the last around 3,000 BC.

Translated from the French and adapted by Anne-Marie de Grazia

Based mainly on the article http://www.hominides.com/html/lieux/grotte-de-niaux.php

as well as on:

Jean Clottes, Robert Simonnet, Le réseau René Clastres de la Caverne de Niaux (Ariège), Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française, 1972, pp 293-323 http://www.persee.fr/doc/bspf_0249-7638_1972_hos_69_1_8166

https://www.lieux-insolites.fr/ariege/niaux/niaux.htm

http://belcikowski.org/ladormeuseblogue/?p=7309

with personal additions.

Articles in Q-MAG.org

Cyprus salt lakes exonerate Peoples of the Sea from destroying Bronze Age civilizations

Toppling Rome's obelisks and aqueducts

Trevor Palmer's response to Gunnar Heinsohn

Jan Beaufort: Conspiracy or religious history?

Gunnar Heinsohn's answer to Trevor Palmer

G.H.: Vikins without towns, ports and sails...

Trevor Palmer challenges Gunnar Heinsohn

The excat dates of the deaths of Patroclus and Hector

Lybian rock-art erased by Jihadists

The tsunami that obliterated Doggerland

Miles below ground, live the creatures of the Deep

Navigation systems of migratory birds suffer from electromagnetic fields

G.H.: Charlemagne's correct place in history

The petroglyph sundial of Mount Bégo

Mount Bégo: an electrical mountain