Alfred de Grazia: from political science to quantavolution (1)

by Anne-Marie de Grazia

This is the text of a paper which I was to give at the Conference CELESTIAL CRISIS & THE HUMAN RECORD in Toronto (May 16-19), which in the end I did not attend. The paper remained undelivered. I take this occasion to thank once more the organizers, and especially Andrew Fitts, Bill Mullen and PLANET AMNESIA for having offered me this opportunity to speak about, and reflect upon Alfred, and I hope that, for those who attented and for the many more who are genuinely interested in Alfred de Grazia's work, reading it in the text, as I wrote it, and without having to suffer through my uncouth presentation, will easily make up for my absence.

Anne-Marie de Grazia, Naxos, June, 2016

As this conference has been gracefully dedicated to the memory of Alfred de Grazia, it would be fitting for me to speak about him, and about the way he worked out this concept of Quantavolution, where it came from, so to speak, and to do this in a way, and focusing on things about which I am in a position to say a little bit more than others could.

My purpose is not so much to praise him, or even to do him justice, this is not something for me to do. But because of the unique position he has occupied at the beginning of the neo-catastrophist movement inaugurated by Velikovsky – and which is bringing us all here. He has given us an organizing tool, a structure, and he has filled this structure with his own ideas and speculations, striving to create a coherent whole. And I want to point out, maybe for the first time, the fact that this structure, and this coherent whole, were solidly grounded in his own background in the social sciences.

Thank you, Bill Mullen, for having evoked in numerous circumstances the Spheres of Quantavolution and reminding the assembly here of this basic structure, strong enough to offer a framework for all kind of investigation and theories to hook on to.

And also for tirelessly pointing out the meaning of the words “Spheres” which Alfred clearly defined in contrast to any “-logies.”

To quote him again:

Not, indeed, “a knowledge and a science of a kind of event, but only ...the happening of a kind of event. The event occurs whether or not we know much about it in the way of laws, propositions and even hypotheses. The use of the term or ending “-spheres” implies correctly that we begin with an event and then proceed to define it and make valid and reliable statements about it.”

Thus defining the open approach, both ambitious and modest, to which Alfred was beholden. And with which anyone following him, even part of the way, should be able to find a comfortable place to stand and to interplay with others. There is a lot of work ahead in the field of neo-catastrophism, or quantavolution, and for a long time to come.

In order to complete this concept of “spheres of quantavolution” I would like to point out a clarifying, important, and similarly modest statement which Alfred made about the term “quantavolution” in his last big public speech, at the University of Bergamo in Italy, on October 20, 2001, and which we should keep in mind, when we are considering and appraising the work he has done, or the purpose of quantavolution itself:

“Quantavolution is not a theory which I can express mathematically. It is a cognitive theory, or perhaps only a heuristic theory.”

Which is why I would like to talk to you today of where Quantavolution came from, which is to say, from where Alfred de Grazia came to Quantavolution. Then, I would like to give you some examples of how this heuristic approach has been in many instances caught up with what for want of a better term we will call “conventional science.”

The fact is that Quantavolution is first and foremost “holospheric” or it is not. And it is this very scope which made that, up to a point, it could only be heuristically approached. The fact that, as we will see, today’s conventional science is much more in chime with Quantavolution, in sharp contrast to yesterday’s conventional science, - and by yesterday’s science, I mean the science of the latter part of the 1970s and the first half of the 1980s, that is, the time when the ten books of the Quantavolution Series were being written - tends to validate the holospheric approach: conventional science had simply, at some point in time, taken an erroneous turn, or a series of erroneous turns, out of which it had to extract itself, and it is still working at it. A philosophical, holistic, heuristic reflection “had to” be undertaken at this particular juncture of time and, I would say, it happened to “pass through” Alfred de Grazia, the social scientist, and manifested itself as “Quantavolution.”

At which point, I would also like to point out that, when it came to the field of Quantavolution, Alfred did not define himself as a scientist, but as a “natural philosopher.” A heuristic approach, it can be argued, can be sufficient to provide a philosophy with a scientific grounding.

Otherwise, Alfred was a scientist, but he was a political scientist. And here I would like to raise a point which is important, but which I will not be able to develop more: all philosophy – and here I take the meaning of the word “philosophy” in its broadest sense, as “love of knowledge,” any knowledge, surmises a scientific grounding, a certain conception of the natural world detached, or at least in large part detached from the religious, and the fact is that lately, through the recognition of the validity of the catastrophist perspective, a non-negligible part of established philosophy itself has acquired a whiff of the obsolete, has become dated, because its scientific grounding has shifted.

I will ask for your forgiveness for first telling you a few things about myself, in order to situate myself in this landscape of Quantavolution, and present to you my credentials, so to speak.

I met Alfred de Grazia on the island of Naxos, in Greece, in October 1977. I was 28 and had published my first book five years earlier, a novel, under my maiden name, at Editions du Seuil in Paris. It had received several distinctions, including an award from the Académie Française. I went on to publish three more books with this publisher. I joined Alfred in New York three months later, January 17th, 1978, and from that day on I lived with him, with only negligible interruptions, for 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, in many places, until his death on July 13th, 2014, that is, for well over 36 years.

When I met him, he had just started writing the ten books of his Quantavolution Series, he had started several books at once. When I joined him in New York, he was about halfway through the first book of the series, Chaos and Creation, and had accumulated a wealth of notes to be used for the latter books.

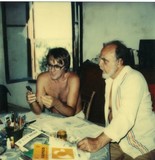

The following month, we were joined for several weeks, in Washington, DC, by Prof. Earl Milton, an astrophysicist from Lethbridge University, Canada, with whom he was working on the theory of Solaria Binaria, which is first expounded in Chaos and Creation. Alfred then wrote God’s Fire – Moses and the Management of Exodus in Naxos, and The Lately Tortured Earth in Washington, DC, where he was working at a project with the National Endowment for the Arts, using the Library of Congress for his research, and where he also invented the word QUANTAVOLUTION, in a little house where we lived at the time in Georgetown, on Q-Street, fittingly (it's the red house).

Chaos and Creation in the Backyard became the title of an album by Paul McCartney in 2005; I have no idea if Paul McCartney has any knowledge of Al’s book. But the first song of the album is rather fitting to our enterprise of Chaos and Creation…

“It’s a fine line

between recklessness and courage

It’s a long way

from Chaos to Creation…

It's a long way, and every contradiction

Seems to say it's a gamethat you're bound to loose..."

In 1980, Earl Milton came to spend two months with us in Naxos, Greece, together with his wife and his little son. Two months during which most of the book Solaria Binaria was written.

I would like to remind you that the Quantavolution Series was written against the heady scientific backdrop of the Voyager II missions. It had met Jupiter in 1979, Saturn in 1981.Those of you who have gone through the experience know what it was like.

The last book of the Quantavolution Series, Cosmic Heretics, was published in May 1984. It was the story of Alfred’s relationship with Velikovsky, and with Velikovsky friends, foes, and followers.

Which means that the actual writing, and publishing of the Quantavolution Series took Alfred seven years, which is both a lot, in terms of one man’s life, and little in terms of the work that got done. He had given up teaching. I was his research assistant, his sounding-board, I typed his long-hand, and worked at selling and sending out books which were ordered by mail. It was an unbelievable, wonderful, fantastically interesting time.

It might be interesting to point out what Alfred did once he had finished the job: he did two things, without asking or warning me, and they will tell you more about him than a psychological study.

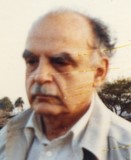

1. He shaved off his beard. He walked out of the bathroom that morning, into the kitchen, with his face shaven clean. It was a shock. It was even more of a shock as he did not smile, nor laugh at my surprise, when all of you who knew him will remember that laughing was very much a second nature to him, certainly when he was in an intimate circle.

2. The second thing, which happened the same day, took me a few hours, maybe a full day to notice: he stopped smoking. Just like this. Without any help or support of any kind. Simply on his will-power, which was awesome. The consequence of the latter decision was a period of frightful mood swings, which lasted for months. It was the end, I would say, of a seven-year honey moon.

We did a third thing, together, several months later, and it needed a little bit more preparation: on December 3, 1984, there occurred a chemical catastrophe at a pesticide plant of Union Carbide, at Bhopal, India. Alfred was very keen on investigating it. We left for India, one month later, on our own, with our own money, without any institutional support, according to one of his mottos: “If you wait for conditions to be perfect, you’ll never do anything.” We spent four months on the spot, investigating, with the help of our friend, Dr Rashmi Mayur, who was a former student of his - who used to call him, affectionately and aptly, his “guru” and who had become one of the first, and most prominent, Indian environmentalists. We retired in a hut in Goa, and later in an apartment in Bombay, and Alfred wrote A Cloud Over Bhopal, which I typed as fast as he was writing on one of the first portable word-processors to appear on the market. The customs officers were so frightened by the machine, when we landed in Bombay, that they made us sign a paper that we would take it back with us upon our departure, or we would not be allowed to leave the country.

We published A Cloud Over Bhopal in Bombay in March 1985, and it has remained the seminal book on the catastrophe. Although Alfred never touched one rupie in royalties. We brought out the book again, thirty years later, a few months before Alfred died, for the thirtieth anniversary of the catastrophe, and we were stupefied to learn that the book had been studied thoroughly almost as soon as it appeared at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales in Paris, in the class of Charles Bettelheim. A whole generation of French Marxist scholars swore by it!

Bhopal was a catastrophe of a most political character, and also of political origins, as the book showed. Which brings us back to where Alfred had actually come from, when he embarked upon catastrophism.

Velikovsky had come from psychoanalysis, and from a Jewish-Russian background in medicine and the sciences. Of his closest followers, those who came from academia hailed mostly from either one of two distinct fields: on the one hand, classical studies, ancient history and archaeology, Egyptology; on the other hand, physics and astronomy, and electrical engineering. Alfred de Grazia came out of left field so to speak, at least out of a field which was practically not at all affected by Velikovsky’s revolutionary ideas.

Which may also explain why Alfred had not heard of Velikovsky until the last days of 1960. He was a political scientist, and quite visible among the political scientists of his generation.

There is a detailed biography of Alfred de Grazia on the site http://kalos.co/ and I will be able to pass quickly over his early life, his studies and his academic career. He was born in Chicago on December 29, 1919, his father was a musician and conductor, born in Sicily. His mother was a second generation American, her own parents having also emigrated from Sicily. Alfred, therefore, had four Sicilian-born grandparents.

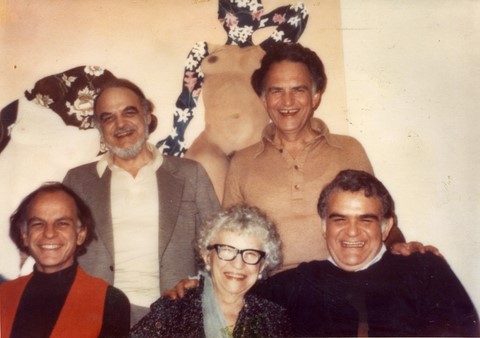

He had three brothers, who all had remarkable careers. Sebastian, winner of the Pulitzer-Prize; Edward, prominent First Amendment lawyer; Victor, Deputy-Governor of Illinois

Standing: Al, Sebastian. Sitting: Ed, the Mom, Vic

(background is a 1970s avant-garde painting owned by Ed)

Alfred studied at University of Chicago, where he had entered on a half-scholarship before turning 15, and had received his PhD phi beta kappa in Political Science in 1948, at age 28, having spent five years in the Army, most of them in combat duty in WWII, in North Africa and Europe.

During WWII, Alfred had belonged to OSS and to the first ever team of the newly created Department of Psychological Warfare. At the end of the war, he was head of the Psychological Operations of the Seventh Army. He continued these activities in the decades following, writing manuals of operations for the CIA, which were classified, and dealt mostly with finding out and dealing with elites in foreign countries. He returned to work in the field during the Vietnam War, with the assimilated rank of a general. At the end of the 1960s, he also undertook several missions for psychological operations in Vietnam, at the time of the Vietnam War, with the assimilated rank of a general, together with his friend Ithiel de Sola Pool, who would become the author of the visionary Technologies of Freedom (1983).

Last year, after his death, I was invited to accept on his behalf the Medal of Distinguished Member of the Regiment of Psychological Operations in Fort Bragg, North Carolina

And, just as I was amazed to discover that the most prominent Marxists in France had perused A Cloud Over Bhopal, I learned with astonishment that his manuals were still very much being used as teaching material at the John F. Kennedy School of Special Operations, something which he was totally unaware of, and which would have surprised him no end…

General Eric Wendt handing me Alfred's Distinguished Member of the Regiment (of Special Operations) diploma,

Fort Bragg, Oct. 31, 2014

As I said already, he did his PhD thesis when he came back from the war, and it was published under the title Public and Republic by Alfred A. Knopf in New York, which was not all too common. It was very well received. It was not his first book, he had published earlier a translation of Roberto Michels’ First Lectures in Political Sociology, from the Italian, with the help of his father.

Alfred A. Knopf commissioned him – he was not yet thirty years old – to write a text book: The Elements of Political Science, which Alfred delivered, in less than two years, in two volumes: Political Behavior and Political Organization. The Elements of Political Science put him unquestionably in the forefront of the new post-war generation of American political scientists.

The Elements of Political Science Publ. Alfred A. Knopf 624p p New York, 1952

Review by Steven Muller, Cornell University

American Quarterly Vol. 6, No 1 (Spring, 1954) pp 88+90-91:

One cannot but receive a work of this scope with admiration. Mr De Grazia has undertaken to dissect the whole body of political science before the uninitiated student. He achieves his purpose with unfailing clarity, and his readers will learn from him the range, the goals, and the techniques of the study of politics as pursued in most American universities.

The book is divided into four parts: scope and method, political behaviour, governmental organization, and democracy and policy. Each chapter has a postscript consisting of questions and problems relating to the material covered and of references to further reading and suggestions for research topics.

Mr. De Grazia defines political science as “scientific method applied to political events.” “Like any other science,” he goes on to say, “it is an attempt to reduce, by ever broader statements, the facts with which it deals to a number of clear, precise, descriptive principles.” This definition sets the tone for the whole volume, and the book will naturally find most accord among those who subscribe to the definition without a qualm.

In 2014, 62 years after its publication, it still ranked 47th out of 161 in Journal Citation Reports (Thomson Reuters, 2015).

He was by then teaching a full load at Stanford University, working with several foundations, and raising a family which grew to seven children. It may seem uncomprehensible that, after such early successes, he was turned down for tenure at Stanford. In fact, he was flagged by the board of trustees for having undertaken a study for the Relm Foundation of "the origins and present restrictions on the political activities of workers," as explained by Rebecca S. Lowen in her book Creating the Cold War university: the transformation of Stanford, published in 1997 by University of California Press.

He went on to publish several more books in the following years, including a book of poetry. He was extremely disciplined, getting up at five o’clock in the morning, he did that until he was well into his seventies, so that there is really no big mystery to his output. He would write some thirty books in the field of political science, most of them before he even met Velikovsky.

By the time he met Velikovsky, in the winter of 1960-1961 he was teaching at New York University, and living in Princeton, a few blocks from Velikovsky’s own house.

One thing which is important to point out is that, as a political scientist, he was as radical and avant-garde as he would be as a “quantavolutionist” and “natural philosopher.” And he was not a leftist, he was “off-the charts,” and always strove to be. He considered himself a pragmatist, and a follower of John Dewey. He published a book by John Dewey first thing when he returned from the War. He belonged to the “behaviorist” school of the University of Chicago, but he didn’t like the term.

He was the founder and editor of a magazine which had become influential in the field of political science, first called PROD, then The American Behavioral Scientist, ABS for short:

PROD, a journal that some American political scientists – and many of its readers – probably regarded as the authentic spokesman for the newest currents among the avant garde of political behavior. (Heinz Eulau, Behaviorism in Political Science, Transaction Publ., 1969, 2010).

Some of his work was supported by the think-tank The American Enterprise Institute, of which his friend Bill Baroody was the Vice-President, and then President. The American Enterprise Institute was not then the most influential think-tank in Washington, but it was already a remote incubator of what would become the Neocons. The American Enterprise Institute published several of Alfred’s books and articles, on “Apportionment and Representation,” (one of his fields of expertise), and on the role of Congress.

Alfred was a champion of the power of Congress against what he saw as the encroachments of the Presidency, which he called “The Executive Force.”

In a book published in 2010, called On appreciating Congress – the People’s Branch, Paradigm Publishers, Louis Fisher says:

The conservative American Enterprise Institute sponsored a series of studies edited by Alfred de Grazia and published in 1967. The title left no doubt about the commitment to republican government: Congress: the First Branch of Government. De Grazia described Congress as “the central institution of the American democratic republic. Unless it functions well and powerfully, much more so than it has in the past, the road to a bureaucratic state and kind of monarchic government will be opened up.” To those who rhapsodized about the coherence, unity, harmony, and rationality of the president, de Grazia reminded them that the president is “a Congress with a skin thrown over him.” If you look carefully within the executive branch you will see fragmentation, divisions, compromise, and various interests fighting for control. The difference is that the legislative process is largely visible; the executive process is not.

I am going to dwell a little bit on one of his books on this subject, or rather, on the way this book is presented by a reviewer in the American Journal of Political Science - one cannot be more authoritative – and I am dwelling on it because it is proving, in an easy and direct way, the point which I am trying to make here, namely, about his radicalism as a political scientist:

The book is Republic in Crisis: Congress against the Executive Force, it came out in 1965 – after he became involved with Velikovsky, therefore, AFTER The Velikovsky Affair, and the publisher is Federal Legal Publication, Inc., not à “fly-by-night” outfit…

The review is by Prof. Cornelius P. Cotter, of Wichita State University.

Everybody who has known or read Alfred will recognize him in the words of Prof. Cotter:

(…)

De Grazia is sometimes irreverent but always forthright and consistent in his effort to twist the ideological tail of the political science profession.

Outraged reviews of the book, and its treatment in future works on “responsible party government” probably will proclaim the success of his effort.

(…)

Ideas, documents, institutions – indeed an entire intellectual paraphernalia – regarded as hallowed by many, if not most, American political scientists are questioned, even ridiculed, in the book. The 1950 A.P.S.A.-sponsored report, Toward a More Responsible Two-Party System, provides a convenient (if not unusual) point of initial onslaught. He regards it as a naïve compendium of myths and expressions of preference, disguised in the language of scholarship then in vogue. “The people” and “program” – as used in the report, and as favorite words in the lexicon of the discipline – are “mysterious” entities (P.54). And this is true whether they are employed in the advocacy of legislative or executive dominance: “…the executive and congressional populist theories are equally myths. Both rely upon a fictitious ‘people,’ which… does not exist; nor can it exist” (pp.21-22).

(…)

De Grazia finds the Supreme Court a threat to legislative strength. “The Supreme Court has no longer any shame about reading the Constitution as if its words meant nothing” (p.254). Political parties, among their chief functions, help to rationalize “ignorant behaviour.” “The people are diverted by the party into accepting the disappearance of direct democracy, with its attractive but impossible promises, while keeping the myth” (p222).

In effect, the responsible party government advocates, consciously in some cases, without understanding their motives in others, are working towards a MONARCHICAL kind of Executive control of government and policy-making in the United States (pp.20-21).

(…)

“The mass media do not see the issue” of legislative control vs. executive control, “and if some aspect of it strikes them occasionally they do not dwell upon it” (p.254). The people generally are President-oriented, rather than Congress-oriented. The tendency towards a larger presidential than congressional constituency stems not merely from his superior opportunities for being singled out from the herd, but from the kind of a monarchical psychology on the part of the people. “That there is a primitive attractiveness to rule by a single man appears to be a fairly well established anthropological principle” (p.37).

This reviewer has emphasized the polemical aspects of Professor De Grazia’s work with the frank purpose of titillating reader interest in the book. What may seem to some egregious statements, and to others, way-out proposals for change, are consciously contrived efforts on the author’s part to stimulate and lay the foundations for a re-examination of the balance of power within our national structure of government today.

(…)

De Grazia argues that the Chief Executive is more influenced by the bureaucracy than a force for control and direction of it; that the very pluralist values which so many advocates of responsible party government argue for are more likely to be preserved in a political system having a strong and independent national legislature

These views of Alfred de Grazia are far from forgotten today. A book was published in 2015: The Presidency and Political Science: Paradigms of Presidential Power from the Founding to the Present by Raymond Tatalovich and Steven Schier, who classify him as an “Anti-aggrandizement scholar” and write, in a segment specifically about him:

(…)

Challenging the liberalism of academia, de Grazia doubts that the president can be the tribune of the people, and to call him the “custodian of the public interest or of the national interest is presumptuous,” because he is custodian of a public interest, his own, and that may be popular or not, shared by Congress or not. When de Grazia speaks of the “problem of dictatorship,” he is citing the growth of the executive apparatus. That is to say, “there is a dictator only because the bureaucratic state must have a face.”

Concerning both the “ends” and the “means” of government, Alfred de Grazia is a conservative. His values concerning what government should and should not be doing are explicit, and he much prefers congressional policymaking. He is not troubled … about “oligarchy and seniority” wielding disproportionate influence within the legislative process, because Congress operates principally through the decision system of successive majorities.” By that, de Grazia means that different majorities rule in subcommittees, committees, and the floor of each house of Congress…: “A rich variety of representational forces filters through the system of successive majorities. Neither the presidency, nor the civil service, nor the pressure groups, nor the courts, nor the political party, nor the press could individually or all together duplicate the process and provide the same ‘product mix.’”

(…)

The American Enterprise Institute then published a book of a debate of Alfred with historian Arthur Schlesinger: Congress and the Presidency: Their Roles in Modern Times, in a series called Rational Debates. Schlesinger took the opposite view from Alfred and extolled Presidential power. A decade or so later, Schlesinger actually recanted his views on the superior qualities of Presidential power, and in so doing actually gave in belatedly to Alfred’s arguments.

To my enquiries, early on, as to whether he belonged to the Right or the Left, he would answer that he belonged to neither, or to both, or that the question had no meaning, an answer which was more puzzling thirty years ago than it is today, just as are some tenets of quantavolution… There are a lot of things which “I have heard before,” during my life with Al, and which since have popped up as novelties…

Politically, if I had to define him, consistently, through his whole life, by one word or two, I would say that Al was a staunch republican, by which I do not mean a member of the Republican Party, but a champion of a Res Publica, a Republic, in the government of which the citizens would, ideally, be involved as much as possible, a model which he deemed suitable for the United States, as well as for the world at large. He was basically a staunch defender of free enterprise, as well as of private initiative, including private welfare.

On a narrow, “party” sense, he would answer me that he had been, himself, a Democrat as well as a Republican. Which can easily be verified from his biography: he was a strong supporter and helper of Democrat Illinois Senator Paul Douglas, his teacher and colleague at University of Chicago.

In the 1950s, he was a supporter of Adlai Stevenson and, while he was teaching at Stanford, he ran for the California Chamber of Representatives on the Democratic ticket. He lost. In 1964, he was a supporter of Barry Goldwater in the Presidential Elections. You will notice that Barry Goldwater has an uncanny resemblance with Velikovsky…

He never made a mystery as to who he was voting for: during “my time,” it has been: Walter Mondale, Dukakis, Clinton, Al Gore, Kerry, Obama… and he ended up disappointed in all of them… But he was very basically unhappy with the limited choice offered by the two-parties system, and constantly supportive of attempts by Third Party Candidates, especially Illinois Representative John Anderson, whose advisers he briefly joined. Before that, in the same election, he had supported Barry Commoner. (He had advised the Anderson campaign to strike out from the beaten path by establishing their headquarters at the Center of Population of the United States, which was then near Maysville, Kentucky. They did not go for the idea. Nothing ever happened in Northern Kentucky... Except that, on July 27, at the height of the campaign, an earthquake struck... [5.2 on the Richter Scale.])

As told by Alfred in Cosmic Heretics, his first contact with Velikovsky’s ideas was in reading Oedipus and Akhenaton. He had noticed the book when visiting his brother’s home, and had borrowed it. Those of us who know Velikovsky’s work know Oedipus and Akhenaton to be a most compelling read, of an almost mesmerizing effect on the reader (Philip Glass succumbed to it). It is the book in which Velikovsky’s art and genius as a psychoanalyst comes to full display, and this certainly was what captivated Al first. His own mentor was Harold Laswell, who had introduced psychoanalysis into political science and Sigmund Freud was, from his student years on, one of Alfred’s intellectual gods.

As it happens, according to Velikovsky himself, the inspiration to his own revolutionary work came to him in the early months of World War II, as he was sailing from Israel along the Southern coast of Crete, on his way to finding a new home in New York. The boat was then at an almost equal distance from Thebes in Greece and Egyptian Thebes, when the intuition hit him that the story of Oedipus may have derived from the story of Akhenaton. Later on, Velikovsky confided to Al that he had been deeply upset by Sigmund Freud’s last book, Moses and Monotheism, published a few months before, in which Freud makes Moses to be a follower of Akhenaton and a copier of his monotheistic revolution. Velikovsky recognized that, in all logic, if it could be proven that Moses had lived before Akhenaton, Freud would be proven wrong and his thesis would be destroyed beyond all hope.

But this entailed putting upside down the whole hitherto accepted chronology of Egypt, Greece and the Near East. The two stories of how his revolutionary ideas came to Velikovsky are perfectly complementary. The hypothesis of catastrophes of an enormous scope – for which there were plenty of clues in the myths and even historical accounts of the peoples of this area – made this chronological overhaul possible, and necessary. For there were obvious problems with the chronologies, and the catastrophic myths, as possible accounts of actual events, were at that time completely discounted by establishment science.

Still, what first interested Al - in a passionate way - about Velikovsky, when he came to know him, was the scandalous censorship and suppression of which his ideas had fallen victim. In other words, it was Velikovsky as a political case. You are probably all familiar with the reception of Velikovsky’s work in the middle of the past century. This scandal - and this is the important point I want to make here - interested Alfred de Grazia as political science, because it was an instance of the play of naked power and interests, but in settings where these power-plays are generally more subdued, more devious, and harder to catch red-handed, namely, academia and publishing. And, moreover, they concerned a most important, and timeless, issue: the politics of science, and knowledge, and the conditions of their progress. The problem, besides, was of paramount importance, considering the leadership position of the United States then, and its stance in the Cold War, particularly the competition with the Soviet Union. The all-important wake-up call, created by the first Soviet satellite, Sputnik, had come just a few years earlier.

By the time Alfred arrived on the scene, the Velikovsky issue had pretty much been relegated to the backburner. To everybody’s surprise - and the horror of many - Alfred decided to dedicate a whole issue of the American Political Scientist to the Velikovsky Affair, including a long and important article by him on “The Reception System of Science.” As a result, the whole matter of the suppression of Velikovsky’s ideas flared up again. This magazine issue was then published in book form: The Velikovsky Affair. This whole story is very well known, and I will pass over it quickly.

It is true that a lot of flak came Alfred’s way in the wake of his taking up the case of Velikovsky, in such a visible way. There has been a romantic misconception, in Velikovskian and catastrophist circles, that it ruined Alfred’s career in academia. Taking the risk to disappoint some of his supporters, I must say that this was not the case. It suffices to have a look at a list of books which he published after The Velikovsky Affair, and of their publishers:

*Republic in crisis: Congress against the executive force (1965), Federal Legal Publications – already mentioned.

*Congress, The First Branch of Government, of which he was the editor, a Doubleday-Anchor Books (1967)

*His debate with Arthur Schlesinger to which I have already referred to: Congress and the Presidency: Their Roles in Modern Times, published by the American Enterprise Institute (1967).

*A text-book: Politics for Better or Worse, published by Scott, Foresman (1973).

* Eight Branches of Government: American Government Today, Collegiate Pub., (1975).

* Eight Bads – Eight Goods: The American Contradictions, published in 1975 as a Doubleday-Anchor Book.

The fact is, yes, he gave up The American Behavioral Scientist, and his visibility as a political scientist diminished somewhat as a result. He sold the magazine in 1965, one year after the Velikovsky Affair, to a young Sara Miller

Sara Miller (later McCune) when she bought The American Behavioral Scientist

In fact, he considered that it was time for him to move on, and he had other projects in the works.

Anne-Marie de Grazia

Naxos, June 2016