Dentistry in the Upper-Palaeolithic

With bread and agriculture came tooth-aches. The hunter-gatherers, living on a diet of meat, fruit, roots and nuts didn’t have to worry much about dental hygiene. But when their descendents became sedentary and cultivated grain, it was the end of healthy ivories. Starches stuck on the teeth, creating a breeding ground for caries.

With the flour, small stones came landing in the bread, on which humans tended to bite off their teeth. In the Neolithic, it seems, dentistry would have had to be invented together with farming.

Not so! A team of scientists around anthropologist Stefano Benazzi of the University of Bologna, in Italy, found proof that the art of dentistry was in fact much older. We know that some 13,000 years ago, someone carried out dental work on someone else's two incisors. That would have been at the end of the Upper Palaeolithic.

The practicioner exerted his art in the mountains of Riparo Fredian, some 75 Kilometer NW of Florence. That’s where, about twenty years ago, the teeth of six individuals have been found under an overhanging slab of rock.

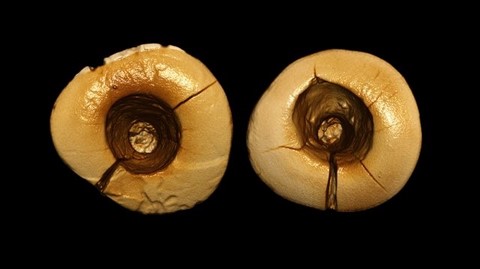

When the team of researchers at Bologna took a new and closer look at the find, they were particularly struck by the incisors of the individual known as Fredian n°5. The protective crowns of the teeth were missing. And in both teeth, the gingival cavities, the holes which hold the nerves, were much larger than normal. „In the case of both incisors, the cavity has been modified during the life-time of the owner," they wrote in The American Journal of Physical Anthropology.

It meant that someone had scraped the interior of the teeth by means of a minutely thin stone, or a bone, in order to remove the spots attacked by tooth-decay - it was the early prototype of the fearsome dentist's drill.

The process must have been incredibly painful, as significant forms of anesthesia still remained to be discovered. At any rate, it is excluded that the traces of scraping on the inside of the teeth could have any natural, spontaneous origin, the scraping scratches are too regular for such to be the case.

The researchers were also able to exclude unhealthy chewing habits, the regular use of the teeth as a tool, or a voluntary modification of the teeth on motives of fashion, or for cultural reasons.

The palaeolithic dentist did not content himself with mere drilling. He carried the job to the end and provided the teeth with a filling. Inside the drilled holes, the researchers discovered rests of a dark substance: they were able to verify that it was bitumen, including traces of vegetal fiber and hair.

"The bitumen may have been used as an antiseptic,“ the scientists speculate in their article, „or it was meant to create an anti-bacterial barrier between the body and its environment.“ The dark, waterproof substance was already used in the Stone Age as a kind of super-glue, for making tools and for waterproofing and caulking. In the Neolithic, we find that teeth which had been drilled were rather sealed with bees' wax.

As for the plant fibers and the hair, they remain until now a mystery. It is not even clear if they were a component of the filling, or if they were rests of food particles which accumulated in the drilling hole over time.

The humans of the Paleolithic knew quite well which plants were able to sooth which conditions. „There exists a good documentation of ethnographic cases on the treatment of tooth aches, caries, root inflamations and other complaints,“ the researchers write.

The patient lived between 13.000 and 12.740 years ago. However, there exists evidence for even older tooth treatment in Northern Italy. Ten years ago, in the province of Belluno in Veneto, archaeologists found a diseased molar, between 14,160 and 13,820 old, the caries of which had also been drilled. However, the work was less precise and there was no evidence of a filling. „The location of the carie, in the hindmost area of the mouth, would have made it more difficult to clean the tooth entirely,“ say the authors of the article apologetically about the old dentist.

However painful the procedure may have been, it seems that the patient lived on untroubled afterwards. Witness to this are the signs of wear at the upper edges of the drilling holes. He probably was able, not only to go on eating, but also to use his teeth as a tool.

"The scratches and the wear on the edges of the dirlling hole allow one to conclude that Fredian 5 survived the exposure of the dental roots and was able to continue to use his teeth for day-to-day activities until his death,“ the researchers write. How he was able to stand the pain of the root treatment is not known. "Unfortunately, I have no answer to that question,“ Benazzi aologizes.

Note of translator: Scientific evidence may be lacking, but one is allowed to surmise that a culture which had figured out and put to use the qualities of bitumen would very likely have discovered (probably even long before) the pain-killing and anesthetic, or perception-altering properties of certain plants. An inflamed root is not easy to bear, either. We must also wonder at the visual acuity and dexterity which this job demanded of the practitioner. In fact, we would think that it is unlikely that the operation was performed on a howling and thrashing, conscious subject.

NEW: The Eternal Embrace

Cyprus salt lakes exonerate Peoples of the Sea from destroying Bronze Age civilizations

Toppling Rome's obelisks and aqueducts

Trevor Palmer's response to Gunnar Heinsohn

Jan Beaufort: Conspiracy or religious history?

Gunnar Heinsohn's answer to Trevor Palmer

G.H.: Vikings without towns, ports and sails...

Trevor Palmer challenges Gunnar Heinsohn

The 1st Millennium AD controversy

The exact dates of the deaths of Patroclus and Hector

Lybian rock-art erased by Jihadists

The tsunami that obliterated Doggerland

Miles below ground, live the creatures of the Deep

Navigation systems of migratory birds suffer from electromagnetic fields

G.H.: Charlemagne's correct place in history

The petroglyph sundial of Mount Bégo

Mount Bégo: an electrical mountain