Did humans split from apes in the Mediterranean?

Meet Graecopithecus freybergi, "El Graeco"

Humans and chimpanzees split from their last common ancestor several hundred thousand years earlier than believed, according to Prof. Madelaine Böhme of University of Tübingen, Germany, and her team.

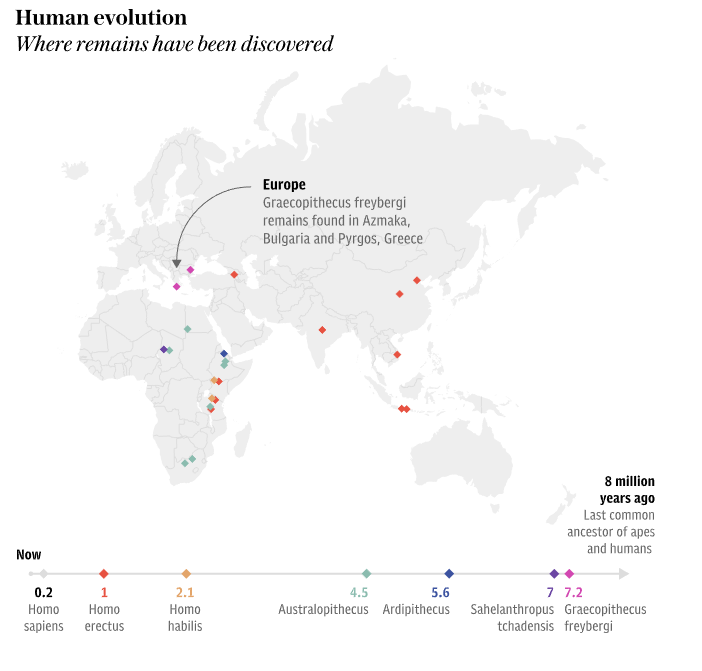

Their findings, published in the journal PLoS ONE, also indicate that the split of the human lineage occurred not in Africa, but in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Currently, most experts believe that our human lineage split from apes around seven million years ago in central Africa, where hominids remained for the next five million years before venturing further afield.

But two fossils of an ape-like creature which had human-like teeth have been found in Bulgaria and Greece, dating to 7.2 million years ago.

The discovery of the creature, named Graecopithecus Freybergi, and nicknamed ‘El Graeco' by scientists, proves our ancestors were already starting to evolve in Europe 200,000 years before the earliest African hominid.

An international team of researchers say the findings entirely change the beginning of human history and place the last common ancestor of both chimpanzees and humans - the so-called Missing Link - in the Mediterranean region.

"To some extent this is a newly discovered missing link, Professor Nikolai Spassov, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences

At that time climate change had turned Eastern Europe into an open savannah which forced apes to find new food sources, sparking a shift towards bipedalism, the researchers believe.

“This study changes the ideas related to the knowledge about the time and the place of the first steps of the humankind,” said Professor Nikolai Spassov from the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences.

“Graecopithecus is not an ape. He is a member of the tribe of hominins and the direct ancestor of homo.

“The food of the Graecopithecus was related to the rather dry and hard savannah vegetation, unlike that of the recent great apes which are living in forests. Therefore, like humans, he has wide molars and thick enamel."To some extent this is a newly discovered missing link. But missing links will always exist , because evolution is infinite chain of subsequent forms. Probably El Graeco's face will resemble a great ape, with shorter canines."

The team analysed the two known specimens of Graecopithecus freybergi: a lower jaw from Greece and an upper premolar tooth from Bulgaria.

Using computer tomography, they were able to visualise the internal structures of the fossils and show that the roots of premolars are widely fused.

"While great apes typically have two or three separate and diverging roots, the roots of Graecopithecus converge and are partially fused - a feature that is characteristic of modern humans, early humans and several pre-humans,", said lead researcher Professor Madelaine Böhme of the University of Tübingen.

The lower jaw, has additional dental root features, suggesting that the species was a hominid.

The species was also found to be several hundred thousand years older than the oldest African hominid, Sahelanthropus tchadensis which was found in Chad.

"We were surprised by our results, as pre-humans were previously known only from sub-Saharan Africa," said doctoral student Jochen Fuss, a Tübingen PhD student who conducted this part of the study.

Professor David Begun, a University of Toronto paleoanthropologist and co-author of this study, added:

"This dating allows us to move the human-chimpanzee split into the Mediterranean area."

During the period the Mediterranean Sea went through frequent periods of drying up completely, forming a land bridge between Europe and Africa and allowing apes and early hominids to pass between the continents.

The team believe that evolution of hominids may have been driven by dramatic environmental changes which sparked the formation of the North African Sahara more than seven million years ago and pushed species further North.

They found large amounts of Saharan sand in layers dating from the period, suggesting that it lay much further North than today.

Professor Böhme added:

"Our findings may eventually change our ideas about the origin of humanity. I personally don't think that the descendants of Graecopithecus died out, they may have spread to Africa later. The split of chimps and humans was a single event. Our data support the view that this split was happening in the eastern Mediterranean - not in Africa.

"If accepted, this theory will indeed alter the very beginning of human history."

However some experts were more skeptical about the findings.

Retired anthropologist and author Dr Peter Andrews, formerly at the Natural History Museum in London, said;

"It is possible that the human lineage originated in Europe, but very substantial fossil evidence places the origin in Africa, including several partial skeletons and skulls.

"I would be hesitant about using a single character from an isolated fossil to set against the evidence from Africa."

The new research was published in the journal PLOS One.

Sarah Knapton

The Telegraph, May 22, 2017

Go to original article in PLOS One.

(Elements added from the article in Science News)

NEW: The Eternal Embrace

Cyprus salt lakes exonerate Peoples of the Sea from destroying Bronze Age civilizations

Toppling Rome's obelisks and aqueducts

Trevor Palmer's response to Gunnar Heinsohn

Jan Beaufort: Conspiracy or religious history?

Gunnar Heinsohn's answer to Trevor Palmer

G.H.: Vikings without towns, ports and sails...

Trevor Palmer challenges Gunnar Heinsohn

The 1st Millennium AD controversy

The exact dates of the deaths of Patroclus and Hector

Lybian rock-art erased by Jihadists

The tsunami that obliterated Doggerland

Miles below ground, live the creatures of the Deep

Navigation systems of migratory birds suffer from electromagnetic fields

G.H.: Charlemagne's correct place in history

The petroglyph sundial of Mount Bégo

Mount Bégo: an electrical mountain